Linux Internals: How ASLR *REALLY* works

Linux Internals: How ASLR REALLY works

Introduction

Nowadays, the security of our programs doesn’t depend solely on the programmer. Modern compilers and operating systems like Linux and Windows implement various mitigations to make it harder for attackers to exploit vulnerabilities - one such mitigation is Address Space Layout Randomization, commonly known as ASLR. In this article, we’ll explore not just the basics but also, thanks to open-source, examine under the hood how each random base address is determined. We’ll see that no implementation is perfect, as developers implementing such solutions must balance security, speed, and simplicity.

Quick Demonstration

Wikipedia tells us: “Address Space Layout Randomization is a computer

security technique used to prevent exploitation of memory corruption

vulnerabilities. To prevent an attacker from redirecting code

execution, for example to a specific function in memory, ASLR randomly

arranges key data areas of a process in the address space, including

the base of the executable and the positions of the stack, heap, and

libraries.” While this definition is correct, I believe things are

easiest to explain by showing. Let’s take a simple C program printing

the address of a local variable c:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char c;

printf("%p\n", &c);

return 0;

}

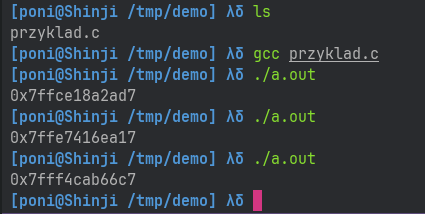

After compiling and running this code multiple times, we can observe that the variable’s address changes each time. This is thanks to ASLR!

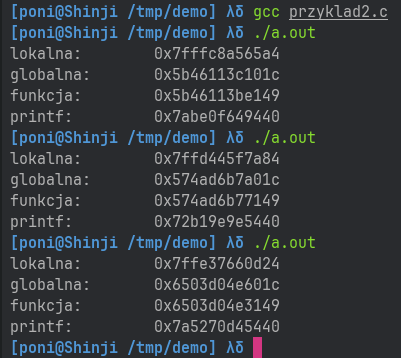

We can repeat the experiment for variables in different memory segments: e.g., local, global, and function addresses.

#include <stdio.h>

int globalna;

void funkcja(void) {}

int main() {

int lokalna;

printf("lokalna:\t%p\n", &lokalna);

printf("globalna:\t%p\n", &globalna);

printf("funkcja:\t%p\n", &funkcja);

printf("printf: \t%p\n", &printf);

return 0;

}

And the result:

Observant readers can already spot some imperfections, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves :).

The Cake - Position Independent Executable (PIE)

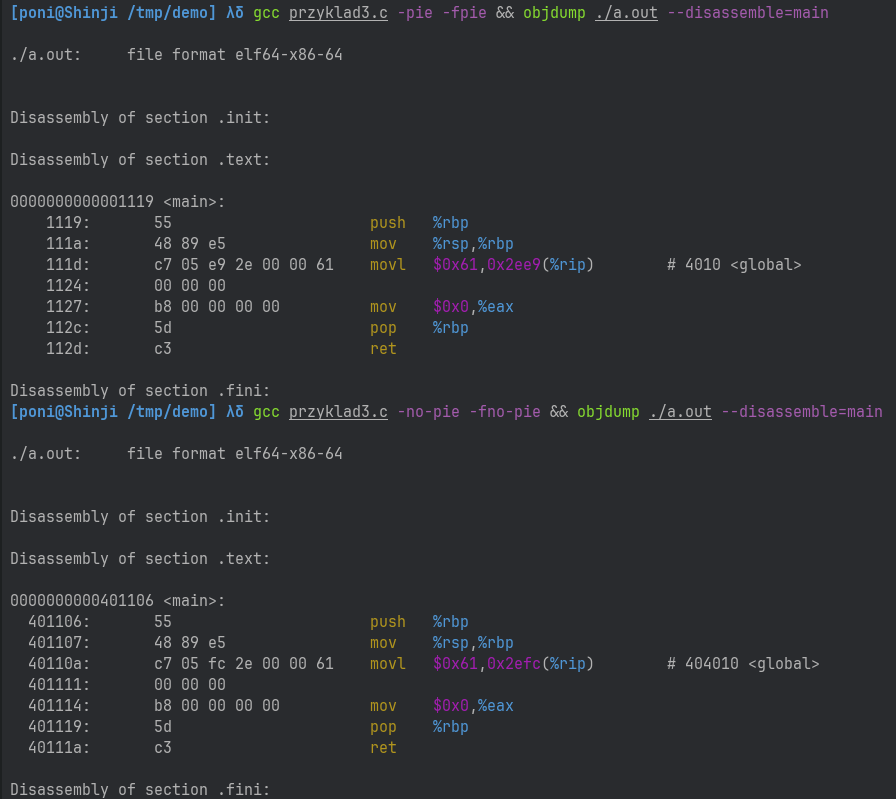

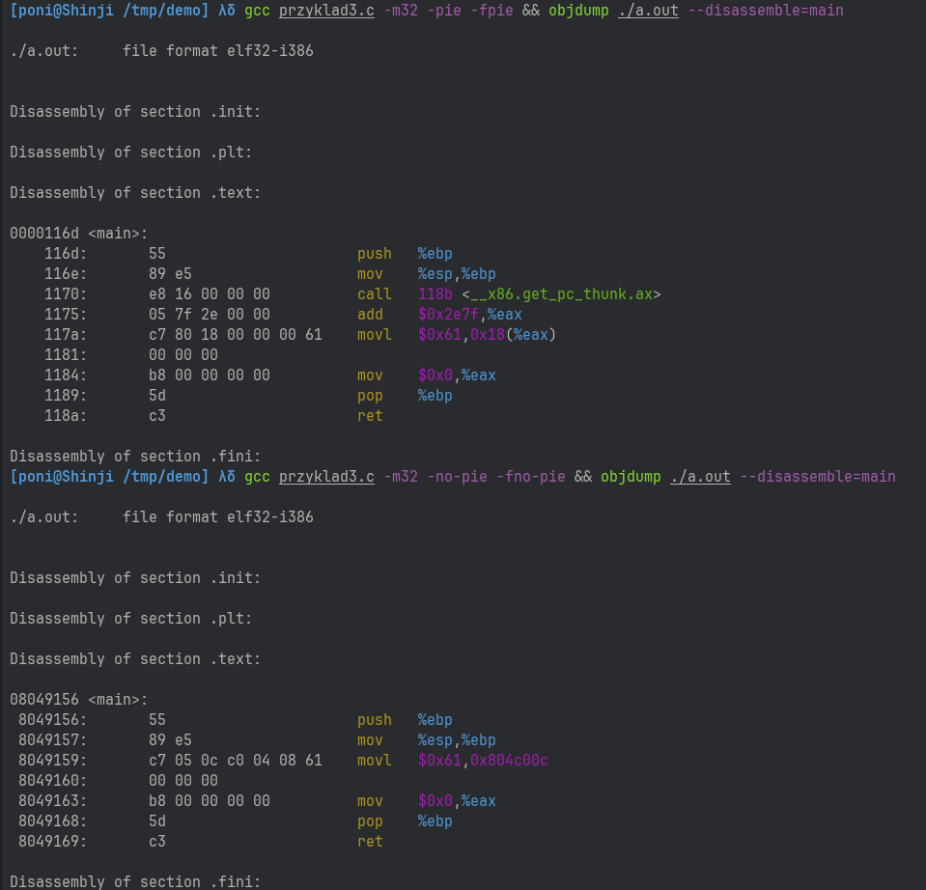

ASLR presence alone isn’t enough. For an executable to be loaded anywhere in the virtual address space, it must be compiled in a special way to be position-independent. The compiler must avoid absolute addressing and use relative addressing everywhere. Shared libraries have always been compiled with the assumption they wouldn’t know their memory location, but historically this wasn’t always true for executables. For example, let’s take this program and compile it in different ways:

int global = 0x41;

int main() {

global = 0x61;

return 0;

}

For x86-64 64-bit systems, compilation method doesn’t matter - both

cases (at least with my gcc 15.1.1) use RIP-relative addressing: movl

$0x61, 0x2efc(%rip).

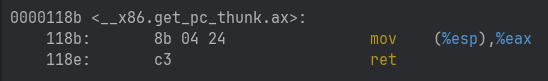

For 32-bit x86 systems, things get more interesting. The x86

architecture lacks EIP-relative addressing, so the compiler works

around this differently for PIE binaries. For no-PIE, we know the

variable address. For PIE, the compiler created a special

__x86.get_pc_thunk.ax function that loads %eip into %eax by

reading the return address from the stack.

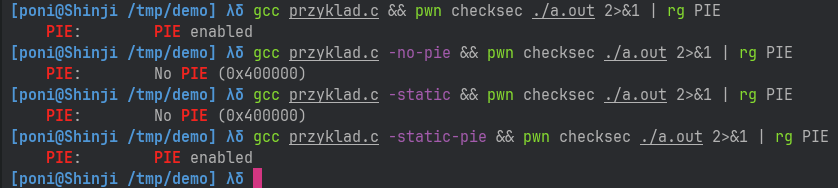

Depending on your distro, PIE may be enabled by default or

not. There’s no standard. According to my tests on Fedora and

OpenSUSE, -pie and -fpie flags aren’t added automatically. On Arch

(which I use), Gentoo, Ubuntu and Debian, these flags are added

automatically… except when using -static! For illustration, we’ll

use checksec from pwntools. Compilation with -static builds without

position-independent code. I’d recommend avoiding this flag and using

-static-pie instead. We lose nothing but a few CPU cycles during

address randomization, while gaining significant security.

Linux Internals

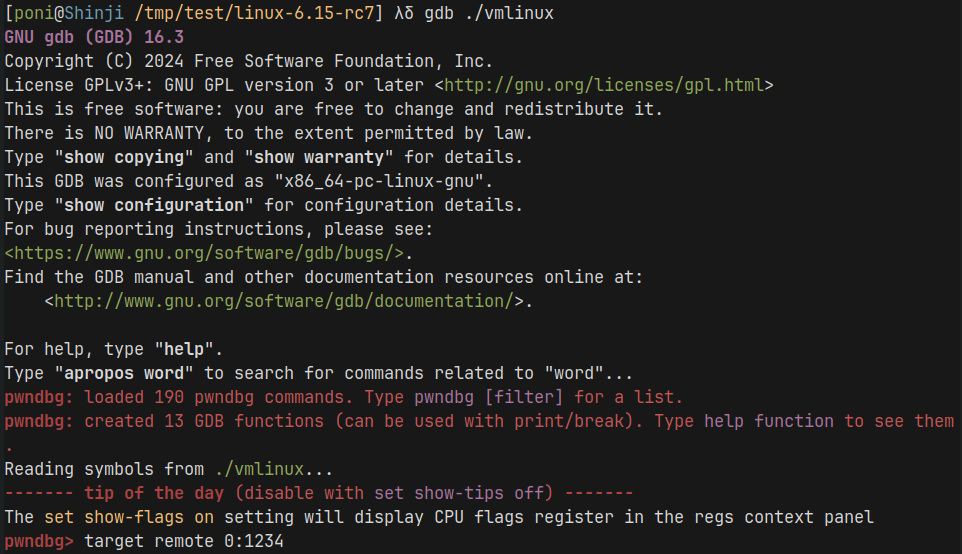

To experimentally see (without just reading code or making assumptions) how addresses are calculated, I built a Linux kernel with debug symbols. By attaching GDB to the kernel running in QEMU, we’ll see the executing code and variable’s values. I encourage you to do this in home!

Prepare the environment

The steps that I’ll do are based on: https://vccolombo.github.io/cybersecurity/linux-kernel-qemu-setup/ . You can skip reading this section if you’re not interested in replicating the experiment yourself.

First install all the dependencies:

# ubuntu

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install git fakeroot build-essential ncurses-dev xz-utils libssl-dev bc flex libelf-dev bison qemu-system-x86 debootstrap

# archlinux

sudo pacman -S git fakeroot base-devel ncurses xz openssl bc flex libelf bison qemu-system-x86 debootstrap

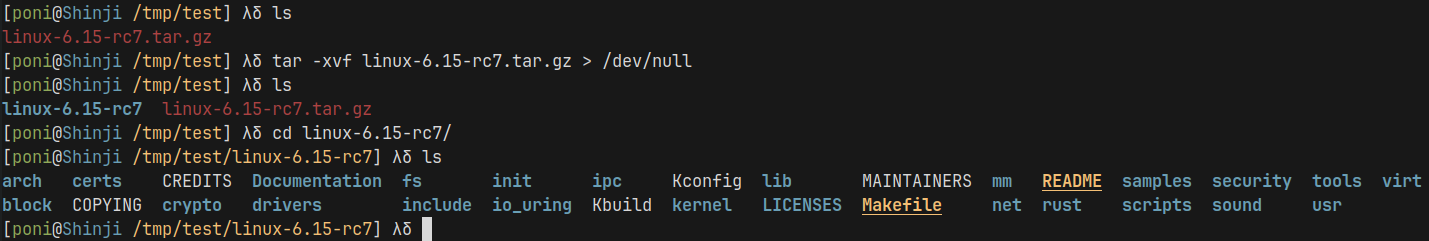

Next, download the latest kernel tarball from https://www.kernel.org/ (6.15-rc7 as of writing), and extract it.

Generate build files with $ make defconfig, then edit the .config

with your favourite editor (in my case Emacs) to add:

# Coverage collection.

CONFIG_KCOV=y

# Debug info for symbolization.

CONFIG_DEBUG_INFO=y

# Memory bug detector

CONFIG_KASAN=y

CONFIG_KASAN_INLINE=y

# Required for Debian Stretch

CONFIG_CONFIGFS_FS=y

CONFIG_SECURITYFS=y

CONFIG_DEBUG_INFO_DWARF5=y

After that, run $ make olddefconfig then compile with $ make

-j$(nproc). This may take 10 minutes to several hours.

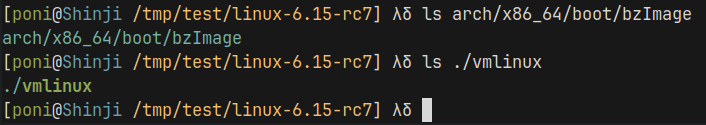

If you’ve never compiled a kernel before, as you can see it’s not

nearly as scary as it might seem! After the compilation is done, two

files should be created: ./vmlinux which is the kernel file with

debugging symbols and arch/x86_64/boot/bzImage, which is the

compressed vmlinux loaded by the bootloader.

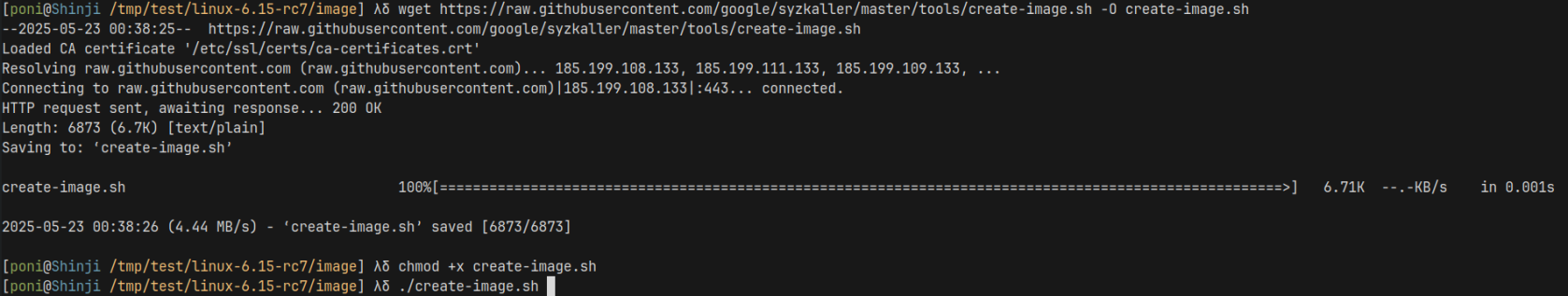

Next, we need to prepare a filesystem image that our compiled kernel will use. We execute those commands:

$ mkdir image && cd image

$ wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/google/syzkaller/master/tools/create-image.sh -O create-image.sh

$ chmod +x create-image.sh

$ ./create-image.sh

that will create a disk image based on Debian.

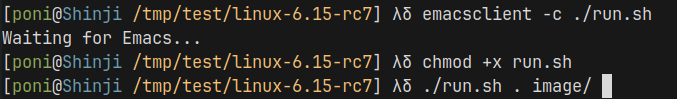

At this point we have everything ready to run the system. We create a

./run.sh file into which we write:

qemu-system-x86_64 \

-m 1G \

-smp 2 \

-gdb tcp::1234 \

-kernel $1/arch/x86/boot/bzImage \

-append "console=ttyS0 root=/dev/sda earlyprintk=serial net.ifnames=0 nokaslr" \

-drive file=$2/bullseye.img,format=raw \

-net user,host=10.0.2.10,hostfwd=tcp:127.0.0.1:10021-:22 \

-net nic,model=e1000 \

-enable-kvm \

-nographic \

-pidfile vm.pid \

2>&1 | tee vm.log

and we run it with:

$ chmod +x run.sh

$ ./run.sh . image/

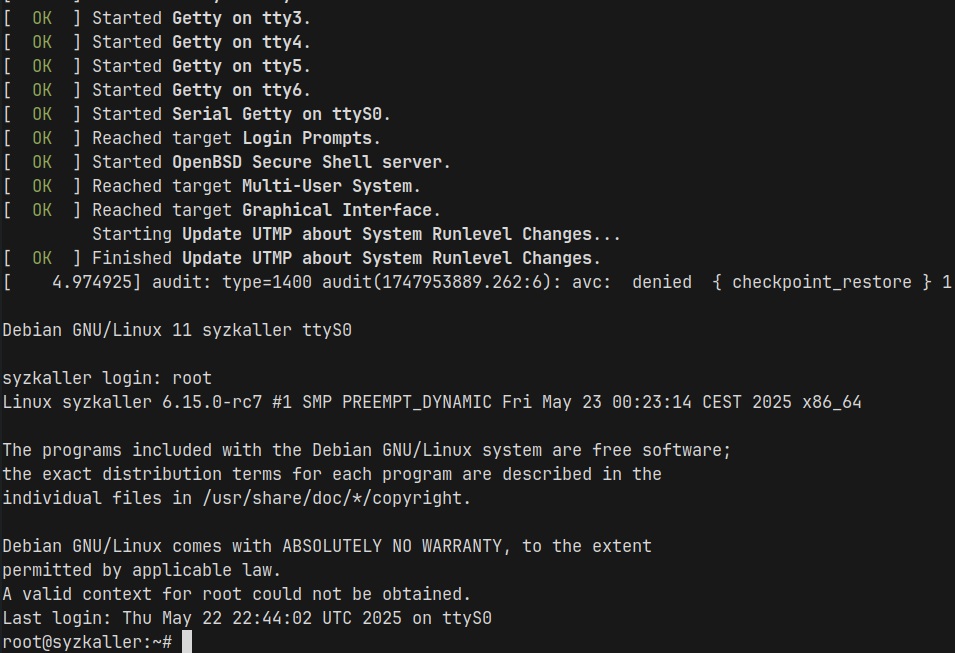

After execution we should see a screen with system login, we log in as the root user, which has no password.

At this point we can connect from a second terminal using gdb to port

1234 provided by qemu. We run gdb with $ gdb ./vmlinux and enter the

gdb command target remote 0:1234.

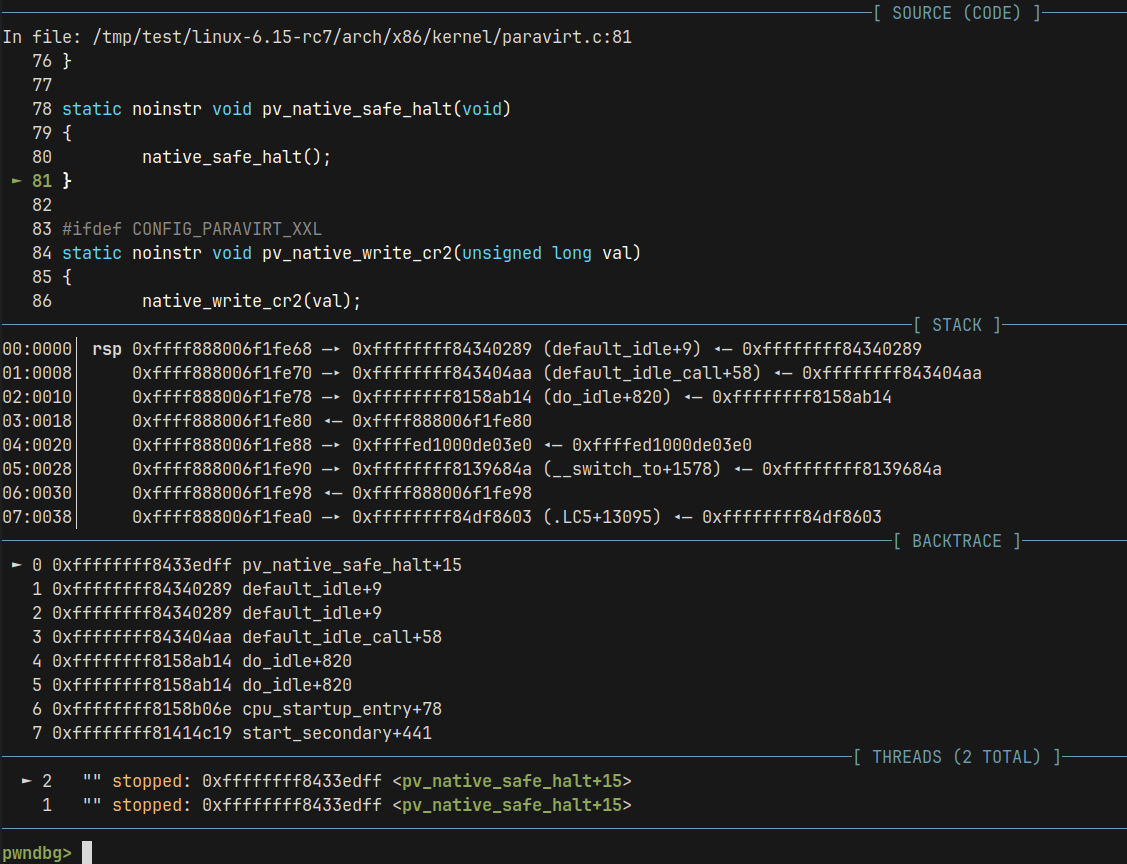

At this point we have gdb connected to the Linux kernel that we compiled, yay! We can execute all the commands we know from debugging programs running in userspace, like breakpoints, stepping and nexting. Additionally I use a gdb plugin pwndbg, which theoretically is created with exploit development and reverse engineering in mind, however I also use it for regular debugging since it makes using gdb easier and I’m used to it. There are also other plugins like gef, or gdb-dashboard, which is more created with regular programmers in mind. I recommend picking one and installing it according to the instructions in the given plugin’s README.

We’re also able to connect to the user inside qemu via ssh, as well as transfer files through scp (which can be useful e.g. to transfer a binary that we compile locally but want to execute inside QEMU).

$ scp -i image/bullseye.id_rsa -P 10021 -o "StrictHostKeyChecking no" ./plik root@localhost:/

$ ssh -i image/bullseye.id_rsa -p 10021 -o "StrictHostKeyChecking no" root@localhost

Deep-dive

The function static int load_elf_binary(struct linux_binprm *bprm)

in the file fs/binfmt_elf.c is responsible for loading executable

files into memory, and it’s precisely from its fragments that we’ll

begin, as randomization starts right here.

To understand how this works in gdb, we set a breakpoint in the

aforementioned function and will run the program $ cat

/proc/self/maps, which will display where all memory segments are

mapped.

Binary

On line 1130 we have code executing for ELF files with ET_DYN (in

other words, these are binaries compiled with -pie -fpie). In the if

condition, we additionally check whether our binary has some

“interpreter”. In the case of ELFs, this is the loader/ld-linux.so,

while in the case of executable text files, the interpreter is defined

by the shebang.

if (interpreter) {

/* On ET_DYN with PT_INTERP, we do the ASLR. */

load_bias = ELF_ET_DYN_BASE;

if (current->flags & PF_RANDOMIZE)

load_bias += arch_mmap_rnd();

/* Adjust alignment as requested. */

if (alignment)

load_bias &= ~(alignment - 1);

elf_flags |= MAP_FIXED_NOREPLACE;

The macro ELF_ET_DYN_BASE equals 0x555555554aaa and defines the

base address (precisely 0x555555554000 after alignment to memory

pages) for PIE loading, to which our program would be loaded if not

for ASLR. This seemingly random value was most likely chosen as easy

to recognize during debugging - the “555” pattern is characteristic

and immediately indicates a PIE binary. Since we have ASLR enabled,

the line load_bias += arch_mmap_rnd(); is additionally executed,

which adds randomness to the address where our program will be

loaded. Now let’s examine this function.

unsigned long arch_mmap_rnd(void)

{

return arch_rnd(mmap_is_ia32() ? mmap32_rnd_bits : mmap64_rnd_bits);

}

static unsigned long arch_rnd(unsigned int rndbits)

{

if (!(current->flags & PF_RANDOMIZE))

return 0;

return (get_random_long() & ((1UL << rndbits) - 1)) << PAGE_SHIFT;

}

The function arch_mmap_rnd calls arch_rnd with the argument

mmap64_rnd_bits or mmap32_rnd_bits, depending on whether our

program is 32-bit. The constant mmap64_rnd_bits equals 28. The

function arch_rnd generates a 28-bit number for us, then performs a

bit shift (PAGE_SHIFT) to align the numbers to memory pages, which

have a size of 4KiB. Example numbers that this function will return

are: 0xe14e215000, 0x110feee000, and 0x6eb8eda000.

The generated number is added to the variable load_bias, which

equals 0x555555554aaa. After adding 0x6eb8eda000 to this variable,

it takes the value 0x55c40e42eaaa. The mask ~(alignment - 1)

equals 0xfffffffffffff000, so after the masking operation load_bias

&= ~(alignment - 1); the variable load_bias equals

0x55c40e42e000. After typing continue in gdb, the cat command

shows us that indeed our program appeared at this location in memory.

root@syzkaller:~# cat /proc/self/maps

55c40e42e000-55c40e430000 r--p 00000000 08:00 12243 /usr/bin/cat

55c40e430000-55c40e435000 r-xp 00002000 08:00 12243 /usr/bin/cat

55c40e435000-55c40e438000 r--p 00007000 08:00 12243 /usr/bin/cat

55c40e438000-55c40e439000 r--p 00009000 08:00 12243 /usr/bin/cat

55c40e439000-55c40e43a000 rw-p 0000a000 08:00 12243 /usr/bin/cat

55c448bc7000-55c448be8000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

...

Heap

Much lower in the same function, at the very end on line 1330, we have randomization of the location where the heap beginning will be found.

mm->start_brk = mm->brk = ELF_PAGEALIGN(elf_brk);

if ((current->flags & PF_RANDOMIZE) && snapshot_randomize_va_space > 1) {

/*

* If we didn't move the brk to ELF_ET_DYN_BASE (above),

* leave a gap between .bss and brk.

*/

if (!brk_moved)

mm->brk = mm->start_brk = mm->brk + PAGE_SIZE;

mm->brk = mm->start_brk = arch_randomize_brk(mm);

brk_moved = true;

}

This value is randomized in the function arch_randomize_brk, which

we’ll examine. The name brk comes from the fact that the place where

the heap is designated is defined by the system call brk. The word

“break” here means “boundary” or “breakpoint” - brk is a pointer in

memory that defines the end of the heap. When a program needs more

memory on the heap, it uses the system call brk and “moves the

break” higher in memory, thereby increasing the available space.

unsigned long arch_randomize_brk(struct mm_struct *mm)

{

if (mmap_is_ia32())

return randomize_page(mm->brk, SZ_32M);

return randomize_page(mm->brk, SZ_1G);

}

unsigned long randomize_page(unsigned long start, unsigned long range)

{

if (!PAGE_ALIGNED(start)) {

range -= PAGE_ALIGN(start) - start;

start = PAGE_ALIGN(start);

}

if (start > ULONG_MAX - range)

range = ULONG_MAX - start;

range >>= PAGE_SHIFT;

if (range == 0)

return start;

return start + (get_random_long() % range << PAGE_SHIFT);

}

In the function arch_randomize_brk we call randomize_page with an

argument depending on whether the program is 32-bit. The function

randomize_page generates a number in the range from start to

start+range (not inclusive). So we’ll generate a number in the range

from mm->brk (which equals the address of the memory page after which

our loaded program ends) to mm->brk+1GiB.

So it might seem that we have an additional 1 Gigabyte (2^30) of

randomness. However, it should be remembered that this address is

aligned to a memory page (4KiB, i.e., 2^12), so 12 bits are

subtracted. Assuming we know the binary address but don’t know the

heap address, we have 18 (30-12) bits of entropy. This isn’t

particularly much and is a certain weakness in ASLR on Linux. This

fact was exploited in this year’s edition of the Break The Syntax

hacking competition in one of my tasks poniponi-virus, which was one

of the more difficult tasks. You can see a write-up

here.

Stack

We determine the stack address on line 1020 in the function

load_elf_binary. Right after the base address to which our shared

libraries will be loaded is determined (which will be discussed

later).

/* Do this so that we can load the interpreter, if need be. We will

change some of these later */

retval = setup_arg_pages(bprm, randomize_stack_top(STACK_TOP),

executable_stack);

if (retval < 0)

goto out_free_dentry;

The function setup_arg_pages takes as one of its arguments the top

of the stack. It should be remembered that in the case of x64

architecture, the stack grows downward (i.e., toward lower addresses),

so we’re actually determining the beginning of the stack. The macro

STACK_TOP equals 0x7ffffffff000.

#define __STACK_RND_MASK(is32bit) ((is32bit) ? 0x7ff : 0x3fffff)

#define STACK_RND_MASK __STACK_RND_MASK(mmap_is_ia32())

unsigned long randomize_stack_top(unsigned long stack_top)

{

unsigned long random_variable = 0;

if (current->flags & PF_RANDOMIZE) {

random_variable = get_random_long();

random_variable &= STACK_RND_MASK;

random_variable <<= PAGE_SHIFT;

}

#ifdef CONFIG_STACK_GROWSUP

return PAGE_ALIGN(stack_top) + random_variable;

#else

return PAGE_ALIGN(stack_top) - random_variable;

#endif

}

The macro STACK_RND_MASK equals 0x3fffff, so we generate a number

consisting of 22 random bits aligned to a memory page. After this, we

subtract this number from the address that would be the top of the

stack if not for ASLR.

int setup_arg_pages(struct linux_binprm *bprm,

unsigned long stack_top,

int executable_stack)

#else

stack_top = arch_align_stack(stack_top);

stack_top = PAGE_ALIGN(stack_top);

if (unlikely(stack_top < mmap_min_addr) ||

unlikely(vma->vm_end - vma->vm_start >= stack_top - mmap_min_addr))

return -ENOMEM;

stack_shift = vma->vm_end - stack_top;

bprm->p -= stack_shift;

mm->arg_start = bprm->p;

#endif

In the function setup_arg_pages we additionally call the function

arch_align_stack, which adds additional random less-significant bits

to our stack. As a result, the stack won’t start at the beginning/end

of some memory page, but in the middle. The rest of the page will

simply be filled with zeros. This two-level stack randomization

(randomization at the page level + fine randomization within the page)

ensures both significant entropy and proper alignment for instructions

requiring specific alignment.

unsigned long arch_align_stack(unsigned long sp)

{

if (!(current->personality & ADDR_NO_RANDOMIZE) && randomize_va_space)

sp -= get_random_u32_below(8192);

return sp & ~0xf;

}

In the function arch_align_stack we can see that we generate a

number less than 8192 (0x2000). So we have 13 random bits. After this,

before returning this number, we mask it with ~0xf, i.e., we remove 4

bits of randomness, ultimately obtaining 9 bits of

randomness. However, one bit overlaps with another bit from the

previously generated number, so in practice we have about 30 bits of

randomness (22+9-1).

Shared libraries and mmap

In the function load_elf_binary on line 1016 we have the function

setup_new_exec, which calls arch_pick_mmap_layout, which in turn

calls arch_pick_mmap_base. In this function we determine the base

address for dynamically loaded shared libraries (such as libc.so.6)

and addresses returned by the mmap system call.

void arch_pick_mmap_layout(struct mm_struct *mm, struct rlimit *rlim_stack)

{

if (mmap_is_legacy())

clear_bit(MMF_TOPDOWN, &mm->flags);

else

set_bit(MMF_TOPDOWN, &mm->flags);

arch_pick_mmap_base(&mm->mmap_base, &mm->mmap_legacy_base,

arch_rnd(mmap64_rnd_bits), task_size_64bit(0),

rlim_stack);

}

/*

* This function, called very early during the creation of a new

* process VM image, sets up which VM layout function to use:

*/

static void arch_pick_mmap_base(unsigned long *base, unsigned long *legacy_base,

unsigned long random_factor, unsigned long task_size,

struct rlimit *rlim_stack)

{

*legacy_base = mmap_legacy_base(random_factor, task_size);

if (mmap_is_legacy())

*base = *legacy_base;

else

*base = mmap_base(random_factor, task_size, rlim_stack);

}

The variable *base is our base address and the value returned by the

function mmap_base is assigned to it.

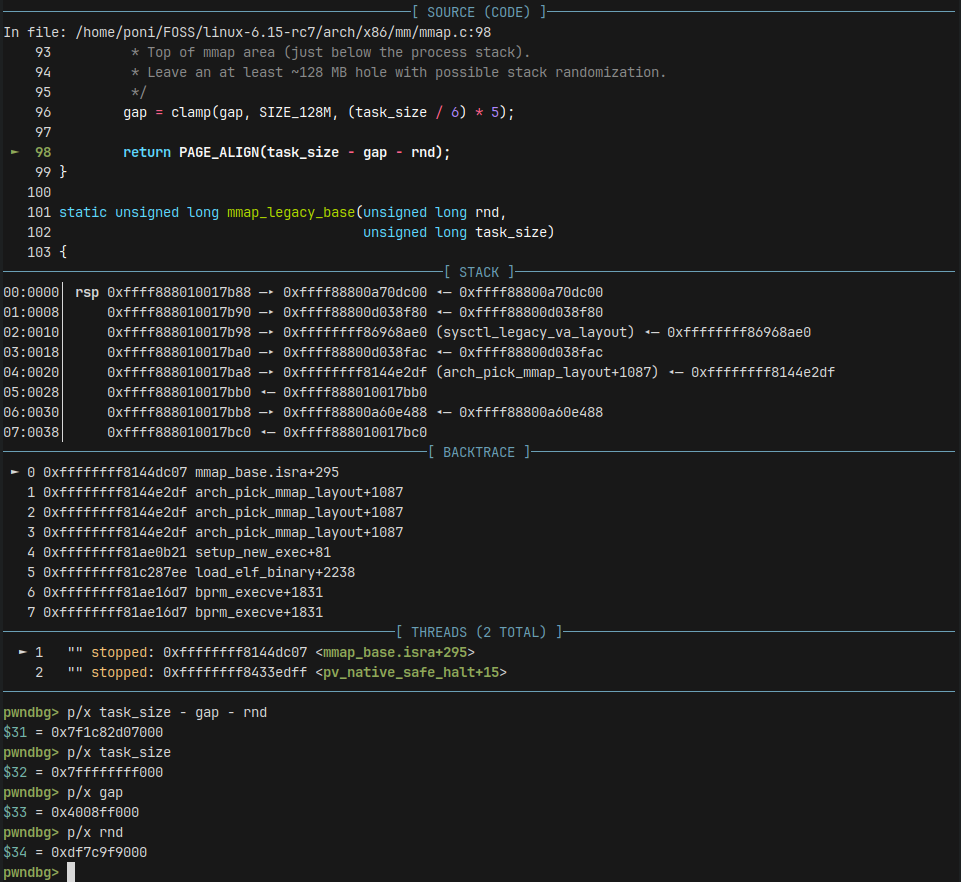

static unsigned long mmap_base(unsigned long rnd, unsigned long task_size,

struct rlimit *rlim_stack)

{

unsigned long gap = rlim_stack->rlim_cur;

unsigned long pad = stack_maxrandom_size(task_size) + stack_guard_gap;

/* Values close to RLIM_INFINITY can overflow. */

if (gap + pad > gap)

gap += pad;

/*

* Top of mmap area (just below the process stack).

* Leave an at least ~128 MB hole with possible stack randomization.

*/

gap = clamp(gap, SIZE_128M, (task_size / 6) * 5);

return PAGE_ALIGN(task_size - gap - rnd);

}

The argument rnd equals the result of arch_rnd(mmap64_rnd_bits),

which was discussed when examining how the binary is randomized and

works exactly the same way. As a reminder, the value returned by this

function gives us 28 bits of entropy.

unsigned long task_size_64bit(int full_addr_space)

{

return full_addr_space ? TASK_SIZE_MAX : DEFAULT_MAP_WINDOW;

}

The argument task_size equals the result of task_size_64bit(0),

i.e., DEFAULT_MAP_WINDOW (0x7ffffffff000), since the function is

called with argument 0.

The base address is determined only once during program loading and

all libraries/mmap system calls depend on it! In the function

unmapped_area_topdown in the file ./mm/vma.c we determine

subsequent addresses returned by mmap and loaded libraries. We won’t

examine this function anymore, as it’s quite complicated and considers

many edge cases.

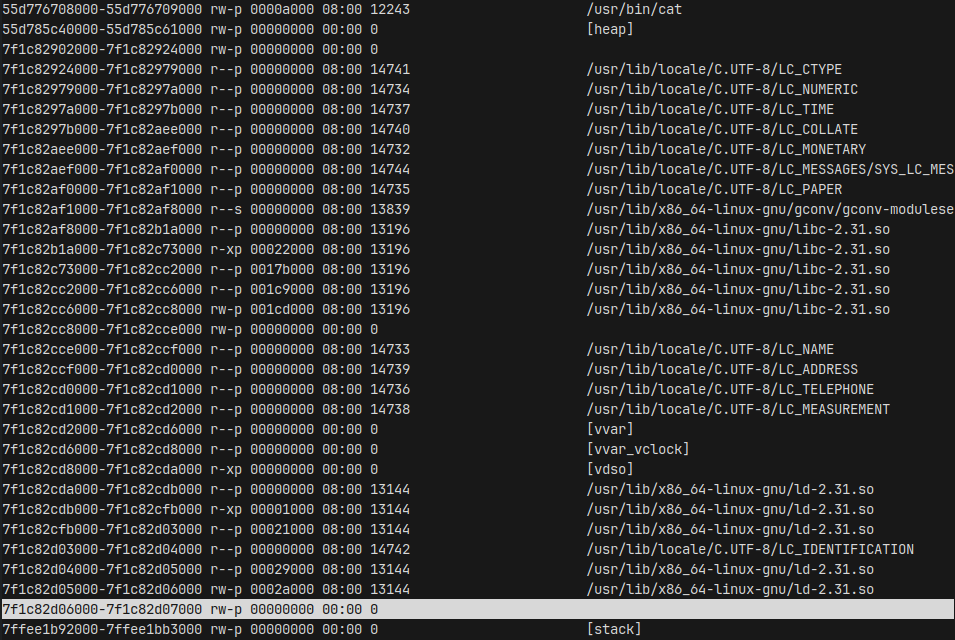

As we can see in the images below:

for the execution of the command cat /proc/self/maps, the function

mmap_base will return 0x7f1c82d07000. This is an address equal to

the end of the last memory segment appearing before the stack. In

practice, it turns out that each time the function

unmapped_area_topdown returns the highest possible address that is

lower than the previous one, so all memory segments “touch each other

and there are no gaps”. As a result, if an attacker knows one address

(e.g., a leak of the address of some anonymous memory call returned by

the mmap system call), they know all other addresses (e.g., the

address of the standard libc library), because the relative offset

remains constant. This is a major weakness in how Linux implements

ASLR.

Comparison with other operating systems

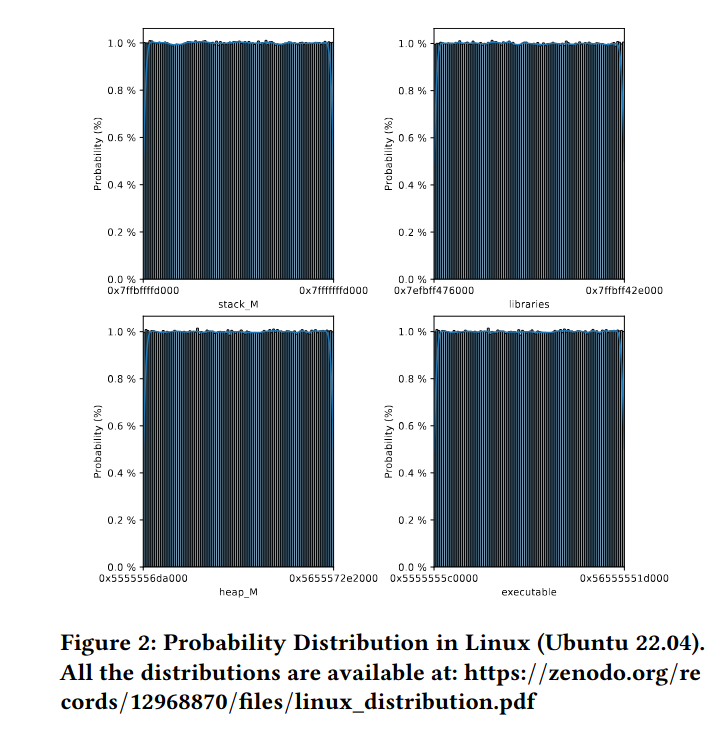

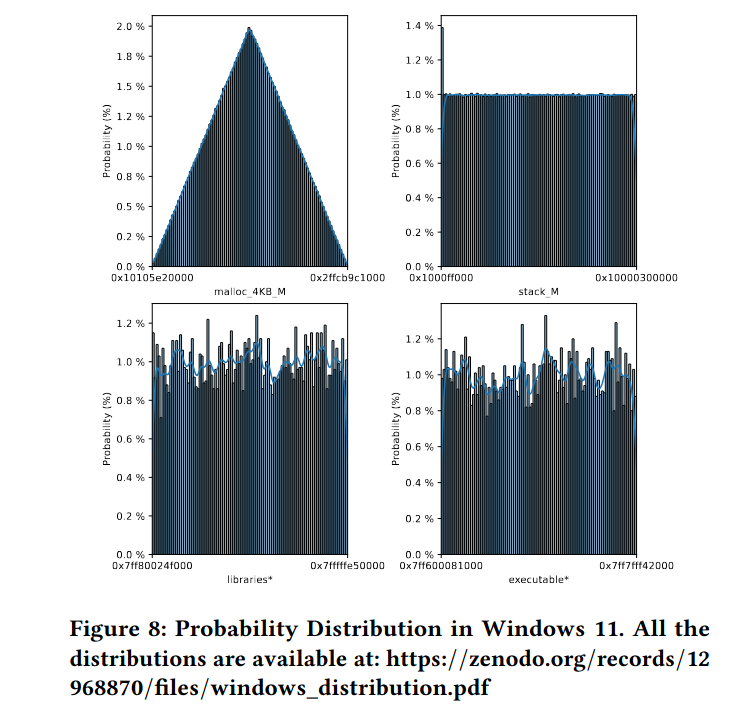

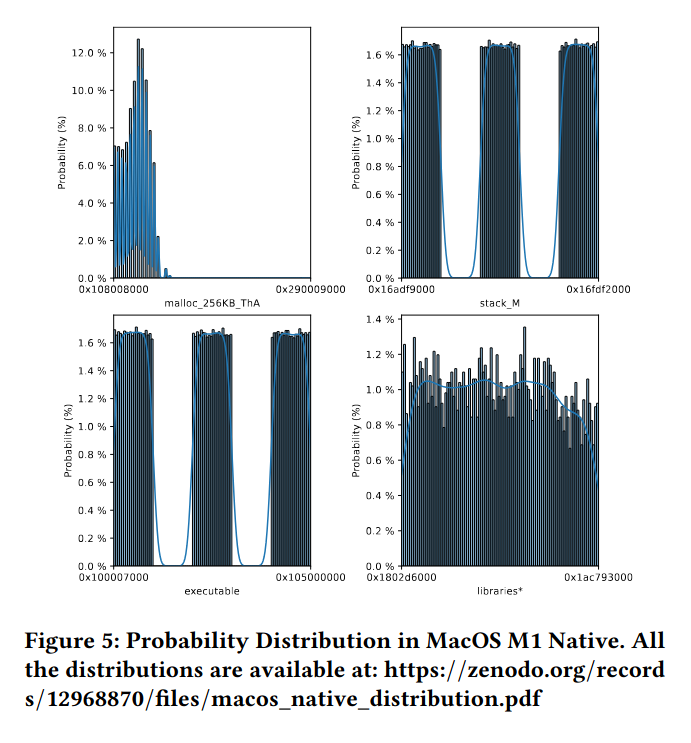

An interesting fact is that ASLR in Linux, unlike Windows and macOS, is the only one that has equal probability distribution everywhere. Research conducted in the paper “The Illusion of Randomness” compared randomness (amount of absolute and conditional entropy bits, as well as distribution) in different operating systems. This is how the distribution looks on Linux:

and this is how it looks on Windows and macOS:

I encourage the curious to read the original paper, as it is very interesting.

Summary

ASLR in the Linux kernel, despite being implemented in a relatively

simple and understandable way, has several significant security

weaknesses. The most important of these are low heap entropy (18 bits)

and deterministic layout of shared libraries, where knowing one

address allows inferring all the others. The implementation is based

on several key functions: arch_mmap_rnd() for randomization of

binaries and libraries (28 bits of entropy), arch_randomize_brk()

for the heap (18 bits of entropy), and randomize_stack_top() and

arch_align_stack() for the stack (about 30 bits of entropy

combined). Each of these mechanisms works independently during program

loading.

Sources

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.15107

- https://sam4k.com/linternals-virtual-memory-part-1/

- https://vccolombo.github.io/cybersecurity/linux-kernel-qemu-setup/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Address_space_layout_randomization

- https://0x434b.dev/an-introduction-to-address-space-layout-randomization-aslr-in-linux/ (a very similar article but has some errors and not everything is showed)

- https://www.kernel.org/

- https://github.com/pwndbg/pwndbg