Intro

In this post I’m gonna compare different security mitigations in Linux and different BSD flavours. Specifically, it’s gonna be FreeBSD, OpenBSD, NetBSD and DragonflyBSD. If you expected MacOS I’m sorry not sorry, I do not have the budget for it. I also could include Windows there but honestly installing Windows feels like a pain for a small blogpost like this. An important thing to note is that this is not supposed to be statement which OS is more secure. This is just an exploration of how different OS’s tackle the most common of mitigation techniques used. Whatever it will look like, if you want a secure operating system you probably should use OpenBSD as it includes a lot of additional security measures, for example my friend silt shared this the other day on our Discord server. Another important thing to note is that everything is done on default settings. I’m sure all the security mitigations can be improved upon by turning on some options but in my defense basic security should be on by default and not be opt-in.

How It Was Done

For compiling on every system I used gcc which as it turned out was in a lot of different versions, some were newer and some were very old. I also used clang just in case to compare but I did not notice any significant differences. The Linux testing was done on my Arch Linux machine but the behaviour shouldn’t differ between distros.

Write XOR Execute

This is not a chapter I expected to make but I was forced to. In every modern operating system there is this rule that a memory page shouldn’t be at the same time executable and writeable. Especially the stack where our local function’s data and different other data like the return addresses from function calls are stored on. When we ignore this rule an older than time itself exploitation technique can be used where we put the code we want to execute as data on the stack and then we return to it by overwriting the return address. Also called shellcoding. Of course it’s not a perfect mitigation, as a countermeasure we have return-oriented programming, but it’s a start. You would expect every operating system with an internet connection to adhere to this rule but no, seems like DragonflyBSD doesn’t care.

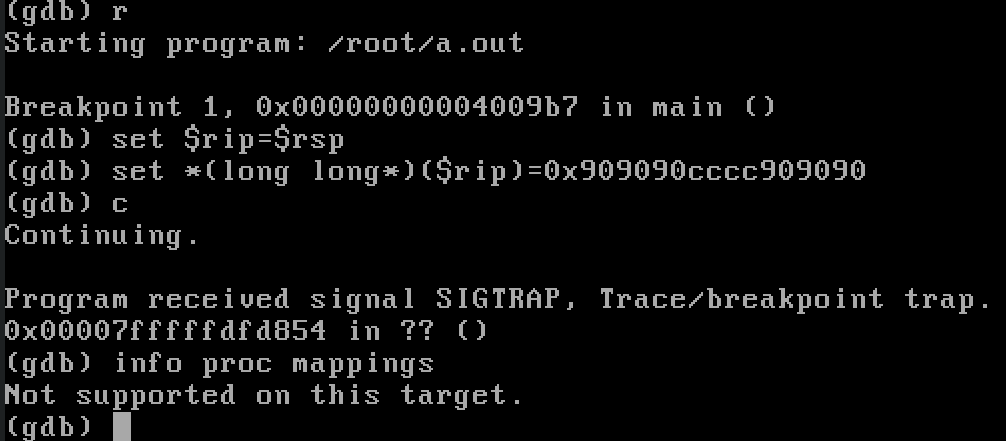

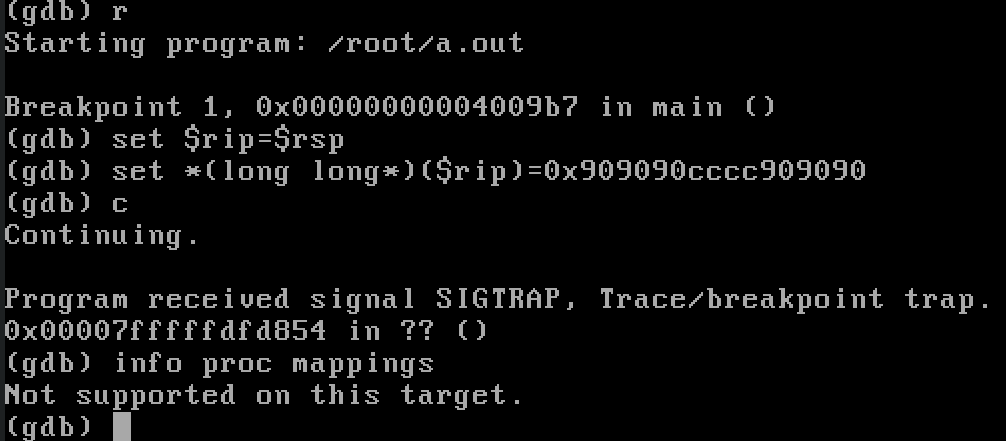

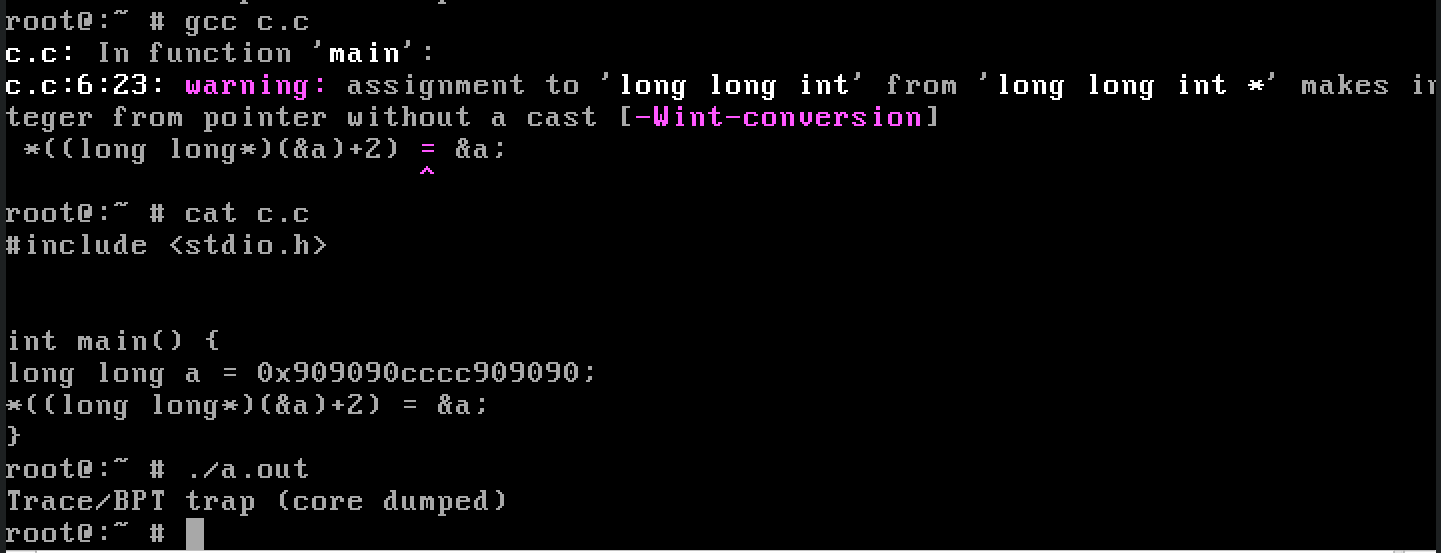

At the beginning I thought gdb is playing tricks on me especially since on DragonflyBSD it didn’t support

At the beginning I thought gdb is playing tricks on me especially since on DragonflyBSD it didn’t support info proc mappings so I couldn’t check what are the permissions of the memory segment, but no. I wrote a small code snippet and I’m perfectly able to overwrite the return address to the stack and execute my code.

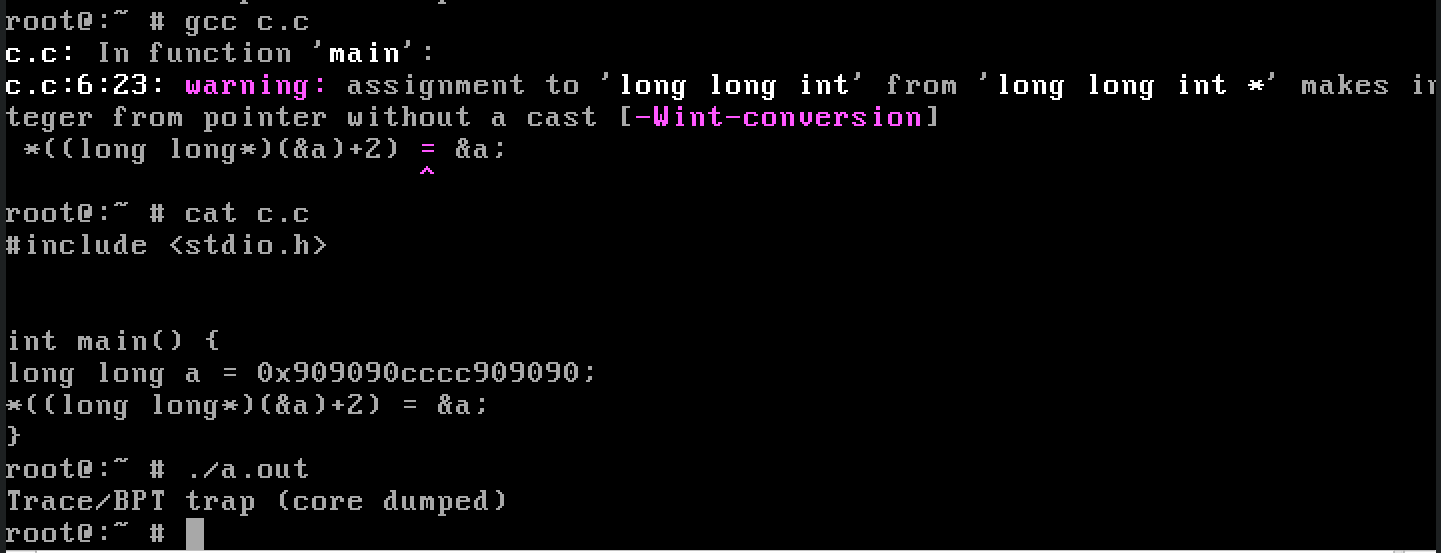

Explanation: at

Explanation: at (&a)+2 there’s stored the return address on the stack, so I’m overwriting it with the address of a which is also stored on the stack. So after the main function returns, we’re executing cpu instructions that are encoded in the number 0x909090cccc909090. Specifically 0x90 is the opcode for NOP and 0xcc is the opcode for INT3 which is an instruction used for implementing software breakpoints. We can see that it’s executed correctly because of the Trace/BPT trap.

ASLR

Now we’re gonna explore everything related to ASLR which is a mitigation that tries to make all of the memory addresses randomized. For testing ASLR I ran a program like this or its variation multiple times:

int main() {

int stack;

printf("bin: %p heap: %p stack: %p libc: %p math: %p\n",

main, malloc(16), &stack, putchar, sin);

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i) {

void *p = mmap(NULL, 0x1000, 6, MAP_ANON | MAP_PRIVATE, -1, 0);

printf("%p\n", p);

}

return 0;

}

This is not a white paper so I’m gonna spare you all the details.

ASLR on Linux

One thing that is unique to Linux is that (at least) glibc uses the brk syscall for creating the heap, while every BSD flavour seemed to use the mmap syscall. I’m not sure if it’s a well known fact but the brk syscall on Linux creates it’s memory segment after our binary and our ASLR only adds some small offset to it. So the security of heap addresses are mostly dependant on the security of addresses of our binary and vice versa.

| i |

bin |

heap |

heap-bin diff |

| 0 |

0x55e801709169 |

0x55e80349c2a0 |

0x1d93137 |

| 1 |

0x556e260b1169 |

0x556e267a72a0 |

0x6f6137 |

| 2 |

0x55a8f6002169 |

0x55a8f765f2a0 |

0x165d137 |

| 3 |

0x5643f11c2169 |

0x5643f2ef52a0 |

0x1d33137 |

| 4 |

0x563ac7313169 |

0x563ac7bfd2a0 |

0x8ea137 |

| 5 |

0x56143239d169 |

0x5614328fe2a0 |

0x561137 |

By looking at the table we can see that the first byte of the binary barely changes and the least significant byte and a half stays the same (this is done so the alignment to memory pages remains the same). By looking at this we can deduce that the randomness only applies to around 4 or 3 and a half bytes giving us 4/3.5 bytes of entropy. Except some very extreme cases this should be more than enough to protect us from bruteforcing the ASLR, especially done through an internet connection. However when we look at the difference between heap addresses and binary addresses only around 1 byte and a half change. In a scenario where the attacker has a leak of our binary it shouldn’t be hard to bruteforce the heap address since there is around 1 in 0xfff (1/4095) chance we will correctly guess the address. In a case where the binary doesnt have position independent code we can even try to guess the address without a leak.

| i |

libc |

math |

math-libc |

1st mmap |

libc-1st mmap |

| 0 |

0x7f0d053ffb20 |

0x7f0d055da620 |

0x1dab00 |

0x7f0d05680000 |

-0x2804e0 |

| 1 |

0x7ff9b973bb20 |

0x7ff9b9916620 |

0x1dab00 |

0x7ff9b99bc000 |

-0x2804e0 |

| 2 |

0x7f51cb692b20 |

0x7f51cb86d620 |

0x1dab00 |

0x7f51cb913000 |

-0x2804e0 |

| 3 |

0x7f2503693b20 |

0x7f250386e620 |

0x1dab00 |

0x7f2503914000 |

-0x2804e0 |

| 4 |

0x7f16f6c12b20 |

0x7f16f6ded620 |

0x1dab00 |

0x7f16f6e93000 |

-0x2804e0 |

| 5 |

0x7fdbdc487b20 |

0x7fdbdc662620 |

0x1dab00 |

0x7fdbdc708000 |

-0x2804e0 |

In case of dynamically loaded libraries we can see that they have the same as our binary around 3.5 bytes of entropy. However different libraries and mmaped memory have the same offset from each other so if we leak one we can calculate the other ones. In this case our mmaped memory appeared after the libc, resulting in a negative number in our difference, but after we mmap enough memory it will start appearing before the libc. This is in fact used in the House of Muney technique which is one of the coolest “house of” glibc’s ptmalloc exploitation techniques.

| i |

stack |

| 0 |

0x7ffdeff02f48 |

| 1 |

0x7ffc6fbded58 |

| 2 |

0x7ffeb6ce9c48 |

| 3 |

0x7fffc896b688 |

| 4 |

0x7ffe5e2e1d08 |

| 5 |

0x7ffcbf1e6c78 |

Stack addresses are independent of any other ones. We can observe that there are 4 bytes of entropy. Fun fact: the randomness at mask & 0xfff0 is done later by adding a random offset to the stack. The least significant nibble is not touched so the stack alignment to powers of 16 remains the same.

ASLR on DragonflyBSD

There by default ASLR doesn’t affect mmaped memory but we can use the sysctl vm.randomize_mmap=1 command to enable it, so I used it.

| i |

bin |

| 0 |

0x1021b3a |

| 1 |

0x1021b3a |

| 2 |

0x1021b3a |

| 3 |

0x1021b3a |

| 4 |

0x1021b3a |

| 5 |

0x1021b3a |

The binary address stays the same even though the binary is compiled as position independent.

| i |

stack |

| 0 |

0x7fffffdfd7bc |

| 1 |

0x7fffffdfda0c |

| 2 |

0x7fffffdfd76c |

| 3 |

0x7fffffdfd86c |

| 4 |

0x7fffffdfd84c |

| 5 |

0x7fffffdfd8bc |

The randomness of the stack is pathetic, combined with the fact that the stack is executable it’s a deadly combination.

| i |

libc |

math |

math-libc |

| 0 |

0xfdd675b05 |

0xfd6bdfdd0 |

-0x6a95d35 |

| 1 |

0xd4a9a9b05 |

0xf27e11dd0 |

0x1dd4682cb |

| 2 |

0xfcd0b8b05 |

0xc64001dd0 |

-0x3690b6d35 |

| 3 |

0xf2f818b05 |

0xff688fdd0 |

0xc70772cb |

| 4 |

0xfdf59cb05 |

0xfdc2fbdd0 |

-0x32a0d35 |

| 5 |

0xff261eb05 |

0x97ac4add0 |

-0x6779d3d35 |

| i |

heap |

1st mmap |

2nd mmap |

3rd mmap |

| 0 |

0xc137d02c0 |

0xfb2fb5000 |

0xfe3938000 |

0xfe3939000 |

| 1 |

0xf832202c0 |

0xfb54fc000 |

0xfb54fd000 |

0xfb54fe000 |

| 2 |

0xe49b102c0 |

0xfff9d7000 |

0xfff9d8000 |

0xfff9d9000 |

| 3 |

0x1000cb02c0 |

0xf85e1f000 |

0xff79a3000 |

0xff79a4000 |

| 4 |

0xfad8202c0 |

0x8781cf000 |

0xfc7986000 |

0xfc7987000 |

| 5 |

0xd5a4402c0 |

0xf93bc2000 |

0xfd0f76000 |

0xfd0f77000 |

The ASLR of the rest looks pretty good.

ASLR on FreeBSD

I hope by now you already see the pattern in which I compare the values. So I will only show the tables without any additional commentary because I would only repeat myself.

| i |

bin |

heap |

stack |

libc |

math |

| 0 |

0x30fc604edaf0 |

0x50521f209000 |

0x3104808556ec |

0x310483062fe0 |

0x3104821b0210 |

| 1 |

0xed517cbaf0 |

0x3faf8fa09000 |

0xf57237cb0c |

0xf5736fafe0 |

0xf572cb6210 |

| 2 |

0x1eda82c45af0 |

0x39fc23a09000 |

0x1ee2a2f2663c |

0x1ee2a3f2cfe0 |

0x1ee2a3846210 |

| 3 |

0x21c3261feaf0 |

0x23d3a0609000 |

0x21cb46afdcac |

0x21cb48b5bfe0 |

0x21cb47b04210 |

| 4 |

0x21e5b4d1baf0 |

0x41c5b2a09000 |

0x21edd52db15c |

0x21edd780bfe0 |

0x21edd6843210 |

| 5 |

0x1cf40b5c4af0 |

0x4d3a05e09000 |

0x1cfc2bd07a0c |

0x1cfc2d6e9fe0 |

0x1cfc2c776210 |

| i |

heap-bin |

stack-bin |

libc-stack |

libc-math |

| 0 |

0x1f55bed1b510 |

0x820367bfc |

0x280d8f4 |

0xeb2dd0 |

| 1 |

0x3ec23e23d510 |

0x820bb101c |

0x137e4d4 |

0xa44dd0 |

| 2 |

0x1b21a0dc3510 |

0x8202e0b4c |

0x10069a4 |

0x6e6dd0 |

| 3 |

0x2107a40a510 |

0x8208ff1bc |

0x205e334 |

0x1057dd0 |

| 4 |

0x1fdffdced510 |

0x8205bf66c |

0x2530e84 |

0xfc8dd0 |

| 5 |

0x3045fa844510 |

0x820742f1c |

0x19e25d4 |

0xf73dd0 |

| i |

heap |

1st mmap |

2nd mmap |

| 0 |

0x4452c5a09000 |

0x4452c6000000 |

0x4452c6001000 |

| 1 |

0x5866d6809000 |

0x5866d6e00000 |

0x5866d6e01000 |

ASLR on OpenBSD

| i |

bin |

heap |

libc |

math |

| 0 |

0xeaa73ce7b00 |

0xeacecb7c2b0 |

0xead3c4151e0 |

0xead270dbdd0 |

| 1 |

0x22ecd4b00 |

0x504b68df0 |

0x4fc7a31e0 |

0x4fb2d3dd0 |

| 2 |

0xa0391ed1b00 |

0xa062f785630 |

0xa061b34c1e0 |

0xa067afcddd0 |

| 3 |

0x4b791e7b00 |

0x4e5fa60900 |

0x4e31c471e0 |

0x4d82904dd0 |

| 4 |

0x60e30f7db00 |

0x610a86e59d0 |

0x610b047d1e0 |

0x6107df94dd0 |

| 5 |

0xa958e007b00 |

0xa979f0821a0 |

0xa981f7791e0 |

0xa983111ddd0 |

| i |

heap-bin |

libc-heap |

math-libc |

| 0 |

0x278e947b0 |

0x4f898f30 |

-0x15339410 |

| 1 |

0x2d5e942f0 |

-0x83c5c10 |

-0x14cf410 |

| 2 |

0x29d8b3b30 |

-0x14439450 |

0x5fc81bf0 |

| 3 |

0x2e6878e00 |

-0x2de19720 |

-0xaf342410 |

| 4 |

0x277767ed0 |

0x7d97810 |

-0x324e8410 |

| 5 |

0x21107a6a0 |

0x806f7040 |

0x119a4bf0 |

| i |

heap |

1st mmap |

2nd mmap |

1st mmap-heap |

2nd mmap-1st mmap |

| 0 |

0x7bde1402210 |

0x7bdd019c000 |

0x7bdf10d4000 |

-0x11266210 |

0x20f38000 |

| 1 |

0xb3c8e37d680 |

0xb3c34247000 |

0xb3c7c6cd000 |

-0x5a136680 |

0x48486000 |

| i |

stack |

| 0 |

0x7f3d689ef9b4 |

| 1 |

0x74a568893c54 |

| 2 |

0x7c986d0dedc4 |

| 3 |

0x7ab552b59574 |

| 4 |

0x7dd201eb02a4 |

| 5 |

0x78bad47c0f74 |

ASLR on NetBSD

| i |

bin |

heap |

stack |

libc |

math |

| 0 |

0xb7c00b60 |

0x753a144fe020 |

0x7f7fff950cfc |

0x753a13d4426e |

0x753a1421c158 |

| 1 |

0xc6c00b60 |

0x6fa617e70020 |

0x7f7ffffe04fc |

0x6fa61774426e |

0x6fa617c1c158 |

| 2 |

0xcb200b60 |

0x76d22e0dc020 |

0x7f7fffff84dc |

0x76d22d94426e |

0x76d22de1c158 |

| 3 |

0xe0200b60 |

0x7eb1b3051020 |

0x7f7fff5b9b8c |

0x7eb1b294426e |

0x7eb1b2e1c158 |

| i |

math-libc |

libc-heap |

| 0 |

0x4d7eea |

-0x7b9db2 |

| 1 |

0x4d7eea |

-0x72bdb2 |

| 2 |

0x4d7eea |

-0x797db2 |

| 3 |

0x4d7eea |

-0x70cdb2 |

| i |

heap |

1st mmap |

2nd mmap |

| 0 |

0x753a144fe020 |

0x753a144ec000 |

0x753a144eb000 |

| 1 |

0x6fa617e70020 |

0x6fa617e5e000 |

0x6fa617e5d000 |

Stack Canaries

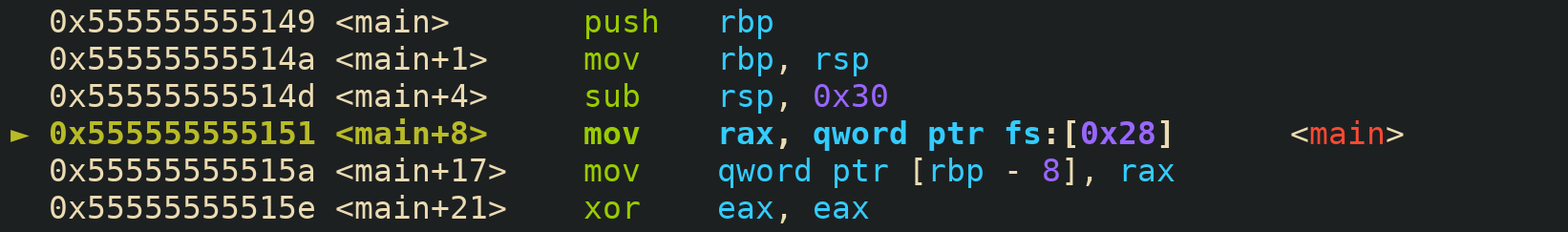

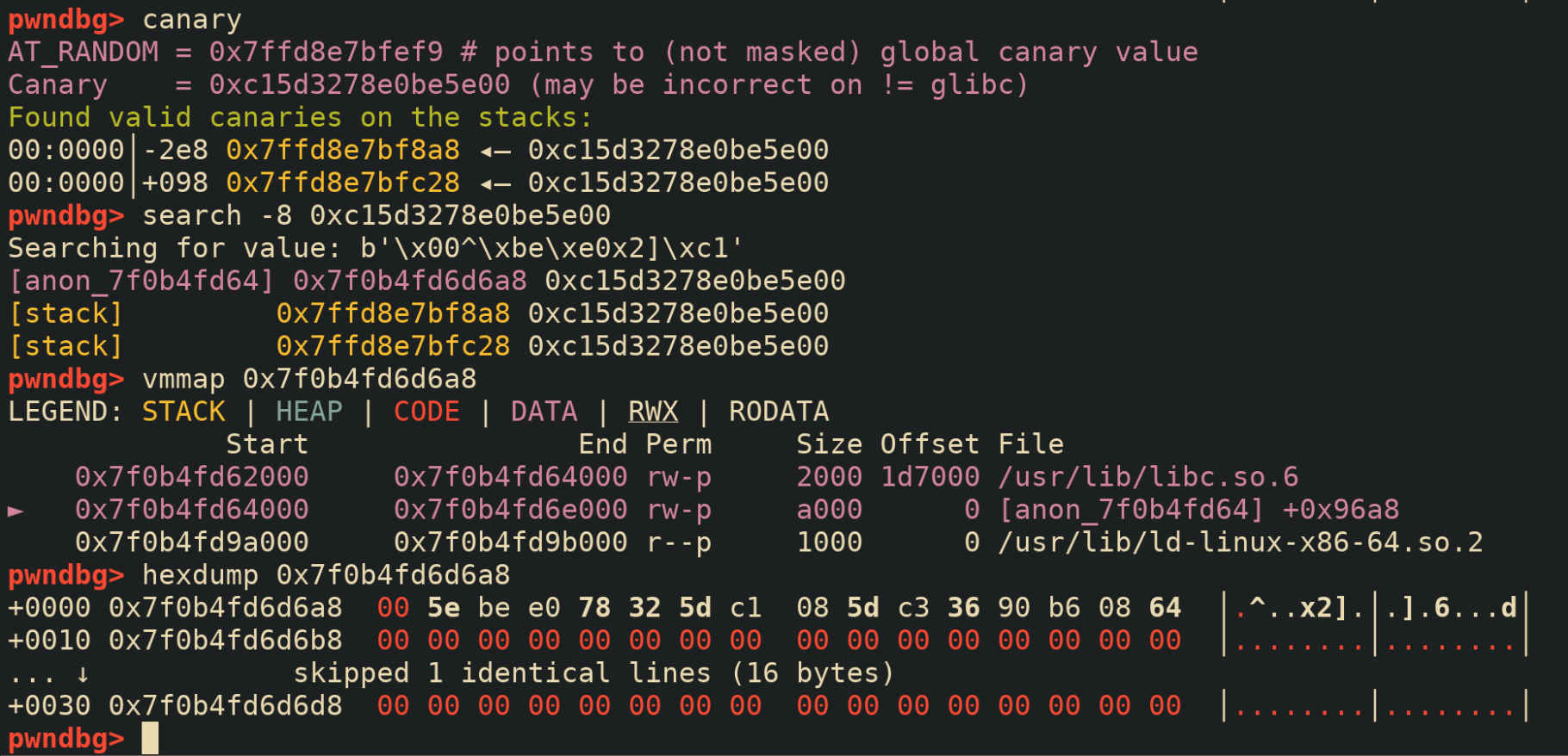

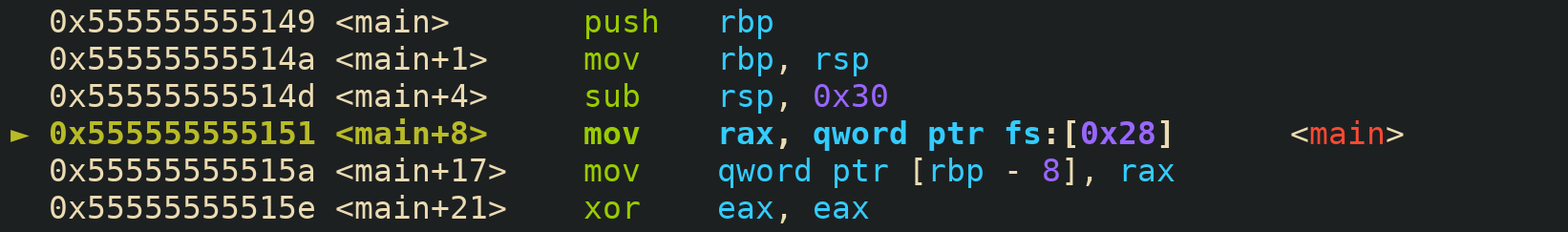

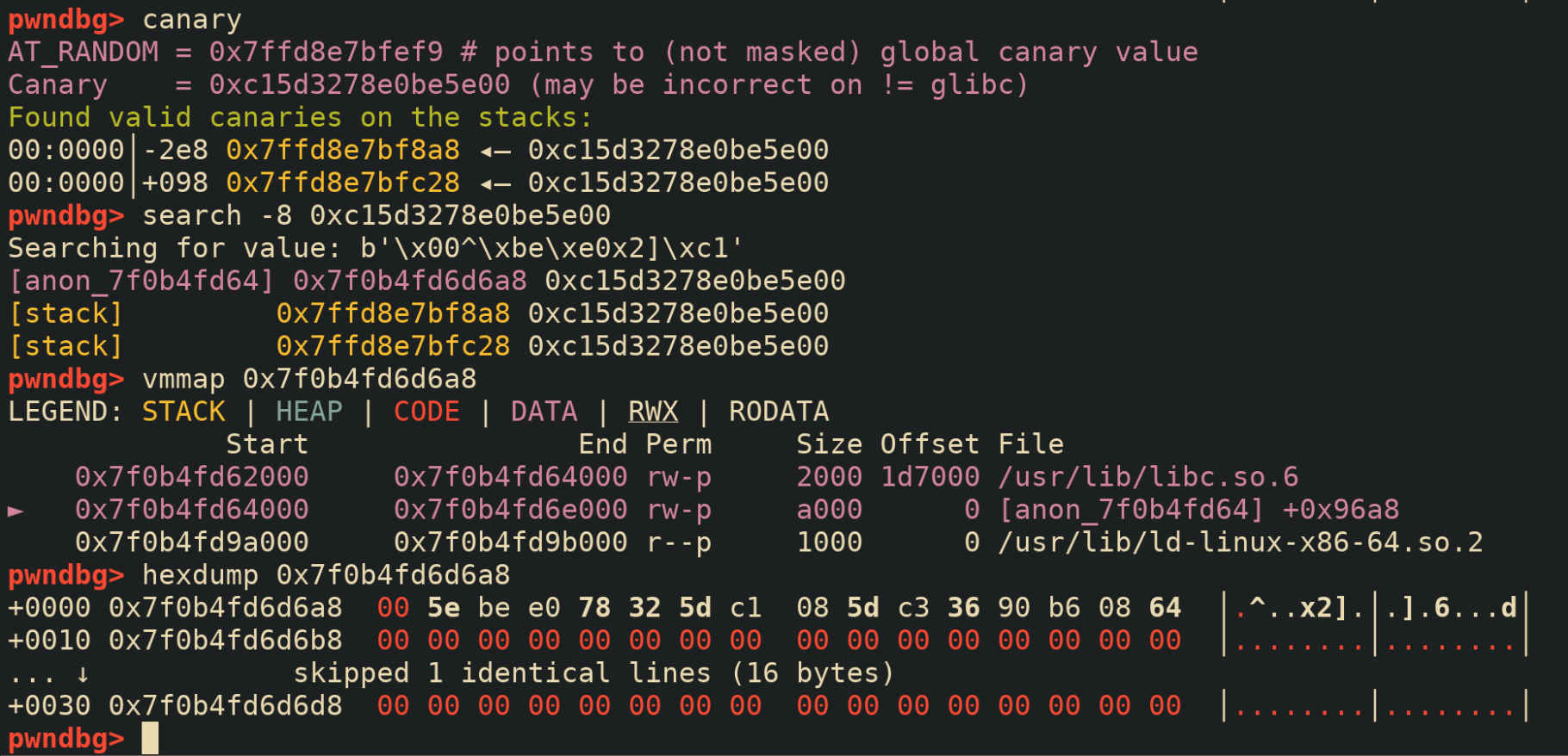

Now let’s talk about stack canaries. I really like the way Linux does them. The first byte of a stack canary is always equal to zero. On a 64-bit system 7 bytes is still more than enough entropy and what we get from the null byte is additional security. Because of it there are scenerios where we for example overwrite N bytes with the letter A, after the letters there’s the canary, and when the letters A are printed we won’t leak the canary because of it - cuz there’s a zero byte separating them. For some reasons only Linux does this. Every other canary didn’t included the null byte. Other thing I like about the way Linux does canaries is that they are located in a special register fs that stores the address of the thread-local storage. Even when we have a write-what-where condition, unless we already have a leak, we won’t be able to overwrite the original canary.

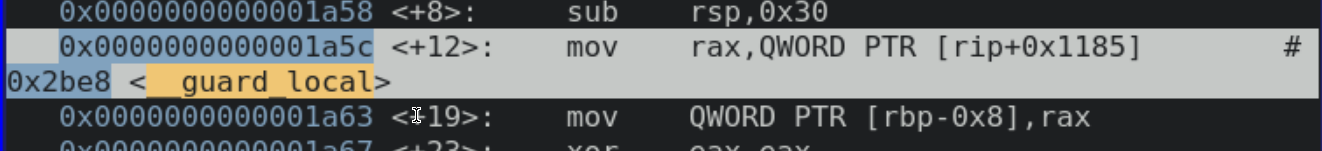

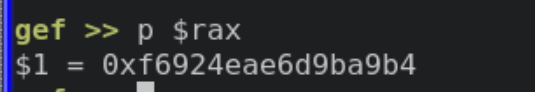

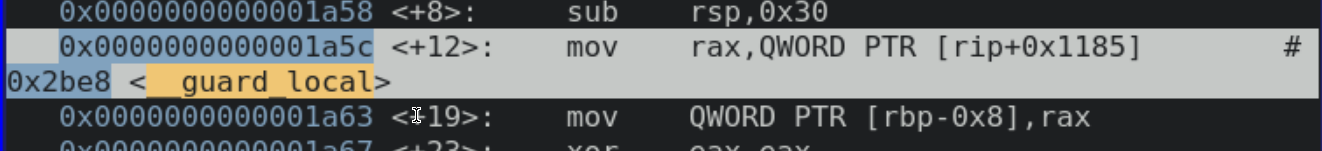

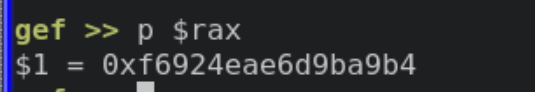

Now, this is not true for all Linux systems. Seems like the GNU toolchain only does this on the x86 and x64 architectures. On the ARM architecture the canary is actually stored inside our binary. To be fair ARM doesn’t have the fs register, but there’s nothing stopping it from using some other one. The same applies for every non-Linux system (including x86 and x64). For example this is how we get the canary inside of x64 on OpenBSD:

Now, this is not true for all Linux systems. Seems like the GNU toolchain only does this on the x86 and x64 architectures. On the ARM architecture the canary is actually stored inside our binary. To be fair ARM doesn’t have the fs register, but there’s nothing stopping it from using some other one. The same applies for every non-Linux system (including x86 and x64). For example this is how we get the canary inside of x64 on OpenBSD:

At the beginning I thought gdb is playing tricks on me especially since on DragonflyBSD it didn’t support

At the beginning I thought gdb is playing tricks on me especially since on DragonflyBSD it didn’t support  Explanation: at

Explanation: at

Now, this is not true for all Linux systems. Seems like the GNU toolchain only does this on the x86 and x64 architectures. On the ARM architecture the canary is actually stored inside our binary. To be fair ARM doesn’t have the fs register, but there’s nothing stopping it from using some other one. The same applies for every non-Linux system (including x86 and x64). For example this is how we get the canary inside of x64 on OpenBSD:

Now, this is not true for all Linux systems. Seems like the GNU toolchain only does this on the x86 and x64 architectures. On the ARM architecture the canary is actually stored inside our binary. To be fair ARM doesn’t have the fs register, but there’s nothing stopping it from using some other one. The same applies for every non-Linux system (including x86 and x64). For example this is how we get the canary inside of x64 on OpenBSD: